Leonardo Bravo:

This is Leonardo and I'm here in conversation with Dianne Smith and Souleo for Kaleidoscopic Projects. It's really great to connect with you both. Dianne, I went to see your exhibition at the Bronx Museum of Art a few months back and I was just so taken by your work and its multidisciplinary mixed media approach to the exhibition project that you had on view, Two Turntables and a Microphone. Souleo, I’ve also been in conversations with you related to other curatorial projects so also wanted to learn more about your practice in the arts and as a curator here in New York. I thought it would be wonderful to have the conversation with both of you and connect the dots a little bit.

Leonardo Bravo:

I wanted to start off with Dianne, I was very impressed with your exhibition at the Bronx Museum and I wanted to find out about the genesis for this. Obviously it's a project you've been working on for a while, but wanted to learn about your approach to working in these very compelling multi disciplinary ways.

Dianne Smith:

Well, I've always wanted to come back home, so to speak, to exhibit in the Bronx. I'd had one exhibition, a public art installation in the Bronx, but the Bronx Museum was something that was on my list of to-dos and spaces to occupy in the Bronx, particularly because I spent a lot of time in that corridor growing up in the South Bronx. We lived off the Grand Concourse. My god-sister lived around the corner, so I was always at her house on weekends. So that was where I spent a lot of my childhood. My aunt lived on 170th Street on the Grand Concourse, just a few blocks up. So it's a neighborhood that I'm most familiar with, and I tend to like being in spaces and communities like the one I grew up in where the idea of fine art, or high art if you will, is not as prevalent in the community or the work doesn't often speak to the people who live in the community.

Dianne Smith:

The institutions are there, but how those conversations happen externally outside of the museum walls is very important to me. And having the community feel heard, listened to, understood, and recognized as having a rich and compelling history. Then there's the other part of me growing up during the seventies into the eighties, and the seventies in particular, where the Bronx was a foreboding place, where the Bronx was burning. And where it was headed for mass destruction. All of that was happening. But on the flip side of that, there were those of us growing up in the South Bronx who was having an experience of joy and community. I grew up at a time when we wandered in and out of each other's apartments.

Dianne Smith:

The doors were left open, and all the little kids played together. We ran the streets all day long like we were going to work in the summertime. Those things were really important. This is the rise of hip-hop, which is coming to life at that point. We were all going to jams, what they called jams in the park back then. I was really young, but we would run off to Crotona Park because we traveled in a group. And go to a jam and watch the MC on the mic and the DJ playing music and spinning records and the circle where people are dancing, and people are going in and out of the circle doing the latest dance at the time. So I wanted to bring all of what I've just talked about into one space and highlight the genesis of hip-hop through my eyes and what I think is the average Bronxonian <laugh>. So that's the genesis for me. Then, in talking to Souleo about it, who is really brilliant at taking what I'm thinking (we’ve had a really great and strong collaboration) and helping me sort of narrow it down and bring it together, package it and take it to the Bronx Museum and them being very excited about it.

Leonardo Bravo:

I love what you say about coming back home and this sense of joy and the feeling of community versus the despair and neglect of the times. And perhaps particularly with what the black imagination can imagine, these worlds that have a sort of generative sense of possibility and reinvention. Also so incredible as well that you were there. You were present at a pivotal moment, the rise of this incredible cultural expression and form.

Dianne Smith:

Absolutely. And it was also for us, like having the vitrine with the contextual information was also really important. Because, as I said, the Bronx was burning, but there was, and I think this still happens today, where there's this undergirding of the assumption that the communities like the South Bronx at the time, or even the community that I live in now, the dilapidation was in fact based on how the inhabitants treated their neighborhoods when that was not, in fact, the truth. Right? It was so easy to blame the community for what it looked like because they lived there, but you know when this is what systemic racism looks like. Systems in place perpetuated these kinds of derogatory perceptions and views. And the media certainly doesn't help.

Leonardo Bravo:

So let's talk a little bit about that collaboration between curator and artist. Souleo, I want to find out about your role as curator for this project, and also how you go about organizing both with the institution and then working and guiding and being of support with Dianne, throughout the genesis of such a project.

Souleo:

So in terms of working with Dianne, like she said, we had a strong and we continue to have a strong collaboration. And so the great thing about working with Dianne is that we both come from a place of like, big ideas, right? We want the work to be big and impactful. We want the message to be big and impactful. And for this project we had a challenge of just one space and trying to contextualize the story of hip-hop in a cohesive way. And so what we were able to do is really focus it on her experiences and using her experiences as sort of the starting point and looking at, well, what is really special about hip-hop.

Souleo:

And it's about its communal aspects, how it brings people together, how it's a vehicle for artistic creative exploration. And then we were able to sort of look at that from her experience, how that reverberates throughout the world and makes hip-hop a really amazing global force. And so my role as a curator, I see it as being, like you said, to support to the artists, from helping to carry supplies <laugh>, to helping navigate the politics of working with institutions - an advocate for the artists. Making sure that the artist has what they need in order to be able to produce the work at the optimal level. In terms of this particular project, it was really exciting to dig through the archival material. Because you know, Diane's got the visuals on lock! I saw my role was how can I support what she's doing visually and add some additional historical context, especially with this being hip-hop and everybody knowing that this was a very momentous year in hip-hop celebration.

Leonardo Bravo:

It's 50 years, right? It originated 50 years ago in the South Bronx!

Souleo:

Yes! So it was really just finding the archive of material to support that and tells Dianne's story. And that puts hip-hop into a historical and sociopolitical narrative as well.

Leonardo Bravo:

That's one of the things I loved about the show the balance between the historical archival materials and its resonance with Dianne's installations, paintings, and sculptural installations and these begin to resonate and amplify that story. It’s so important to have that storytelling narrative component embedded into the project, so kudos to you both!

Souleo:

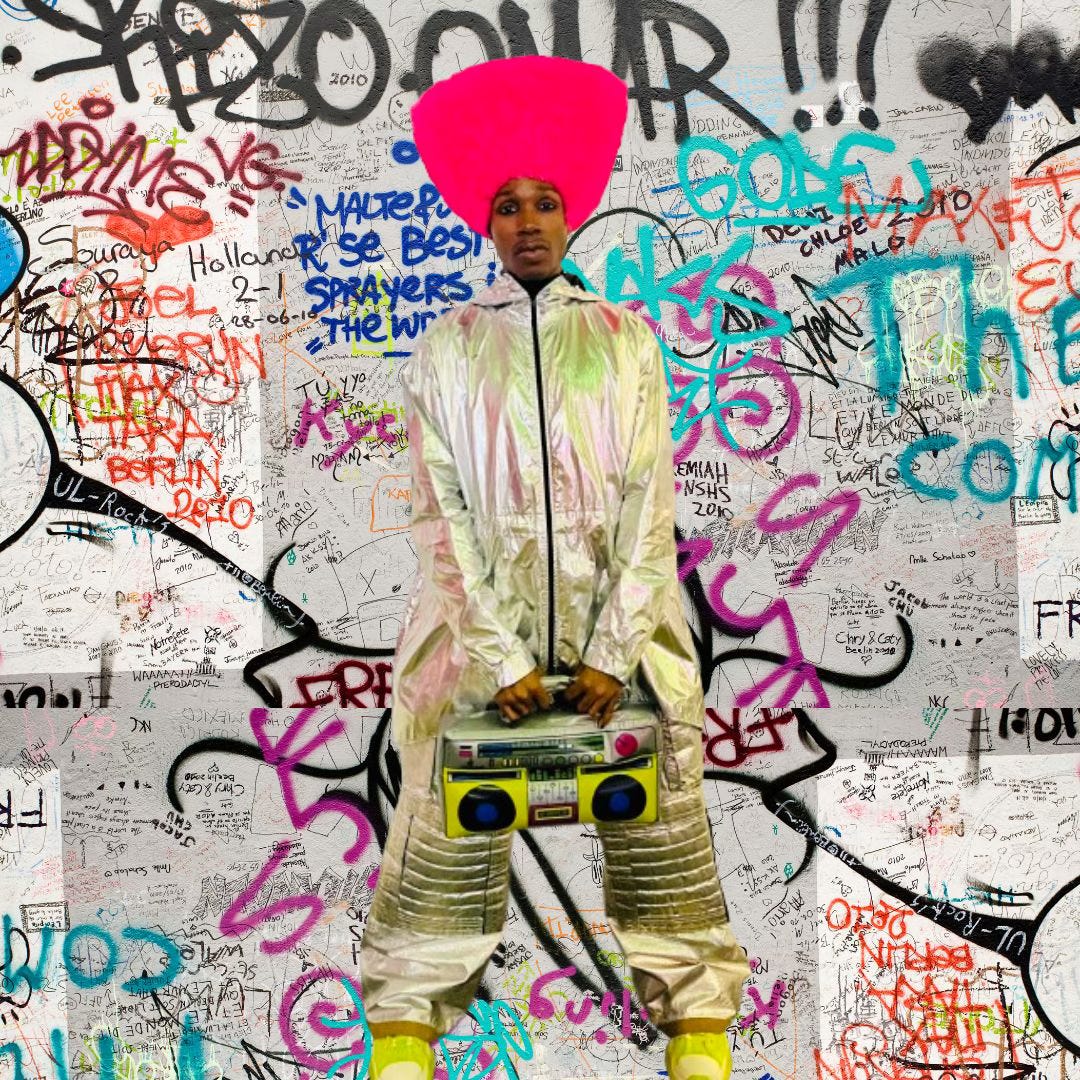

And it was also important to Dianne that she really wanted this to be interactive, right? She didn't want it to be like, you just come and see beautiful works on the wall. We wanted the community to engage. So maybe Diane, you wanna talk more about this, but we had the graffiti wall where people were able to leave their thoughts and comments. She had that amazing video projection where people were dancing in front of it and then the whole two turntables and a microphone that she recreated. People were going behind there, rapping on the mic and everything. So it was really that engagement that we wanted to have as well.

Dianne Smith:

Yeah. It was important for me that the community were not passive viewers of their lived experience. Right. They got to participate, and not just participate but leave their mark because there were so many participants of hip-hop, particularly in that time period, that didn't get to tell their stories. We did not have any expectations of the graffiti wall and what would be left behind. But we ended up with hundreds of postcards. The wall was filled with people leaving their memories, mementos, hopes, dreams, art, and everything related to hip-hop and the exhibition. And we are happy to say that those cards now sit in my archives at Barnard College. Those things will now be accessible for further research and understanding of the importance of hip-hop.

Dianne Smith:

And so we really wanted to bring it back to the community aspect and the idea of joy. It was amazing to see the intergenerational interconnectedness with that. We had a section where there were a bunch of TVs stacked, and then we wrote hip-hop lyrics on the screen, so the screens were blacked out. And we went back and forth on whether or not we would do that, but we were like, no, let's write hip-hop lyrics, positive hip-hop lyrics. It was to mimic the couch in the living room where you sat and watched Yo MTV Raps or Ralph McDaniel's Video Music Box. Or you just sat there and listened to the boom boxes.

Dianne Smith:

Just listening to the boombox or the Walkman was your Friday or Saturday night. Hearing the intergenerational conversations with parents sitting on a couch with their kids, that conversation was really important and what we were hoping to gain and amplify from this exhibition. We were happy that so many people came from other places to see the exhibition. People traveled from outside New York City and other states, they came from other countries to see the exhibition. And again, that speaks to the global reach of hip-hop. What we set out to do with this exhibition is to have a community-engaged conversation about the art form, but understand that community-engaged conversation is about its global impact. So it was really interesting that we were able to do that.

Leonardo Bravo:

This falls into the next question which is about the work that curators and artists and scholars do around reconfiguring and re-contextualizing cultural histories, particularly cultural histories of communities that have been displaced, erased, or marginalized. How are these values and contexts are woven into your practice? Obviously into this specific project, but perhaps how does that inform your larger practice as a curator and as well with you Dianne, I would say the overall kind of lens for your work.

Souleo:

I see my work as a curator as really sort of helping to amplify underrepresented narratives. I think that has a lot to do with, one of the inspirations that got me involved in being a curator, which was my brother, Glenn "Spoof" Wright who was murdered and who passed. And so him being an artist who didn't get a chance to really pursue that professionally was a catalyst for me to uplift his voice. And then from there with my partner Beau McCall and other artists that I wanted to uplift. And so as I went along becoming a curator, I was like, okay, so these are contemporary artists but what about artists from the past? What about stories from the past? Dianne and I also collaborated on the Showing Out Fashion Harlem exhibition where she did a new media piece that's about the Harlem Institute of Fashion, which a lot of people don't know about. And so we wanted to amplify that narrative. So a lot of my work is really just about bringing these stories to greater light because there's so much that is inspiring about what people have done in the past, and especially under the circumstances that they had to do it under, you know, we're talking about segregation. Racism. And a lot of these things continue, but it's helpful to look back and see if they were able to do it then, then that gives us the strength and inspiration, courage to do it now.

Dianne Smith:

So that's always great because I have not just historical documentation that I can get, but I have my own historical memories. My own ways of reaching back and saying, okay, this is what has been written, but this is my experience in conjunction with that. In short, it is just really creating from my lived experience finding the value and the beauty in all that, and being present for it. My understanding as I grow older is that we are doing something of importance, and it is part of history, and all of us, in our own way, have a mark in history. My voice is for the person who has done things that may not be an artist and not have the outlet, but they have done similar things that I have done.

Dianne Smith:

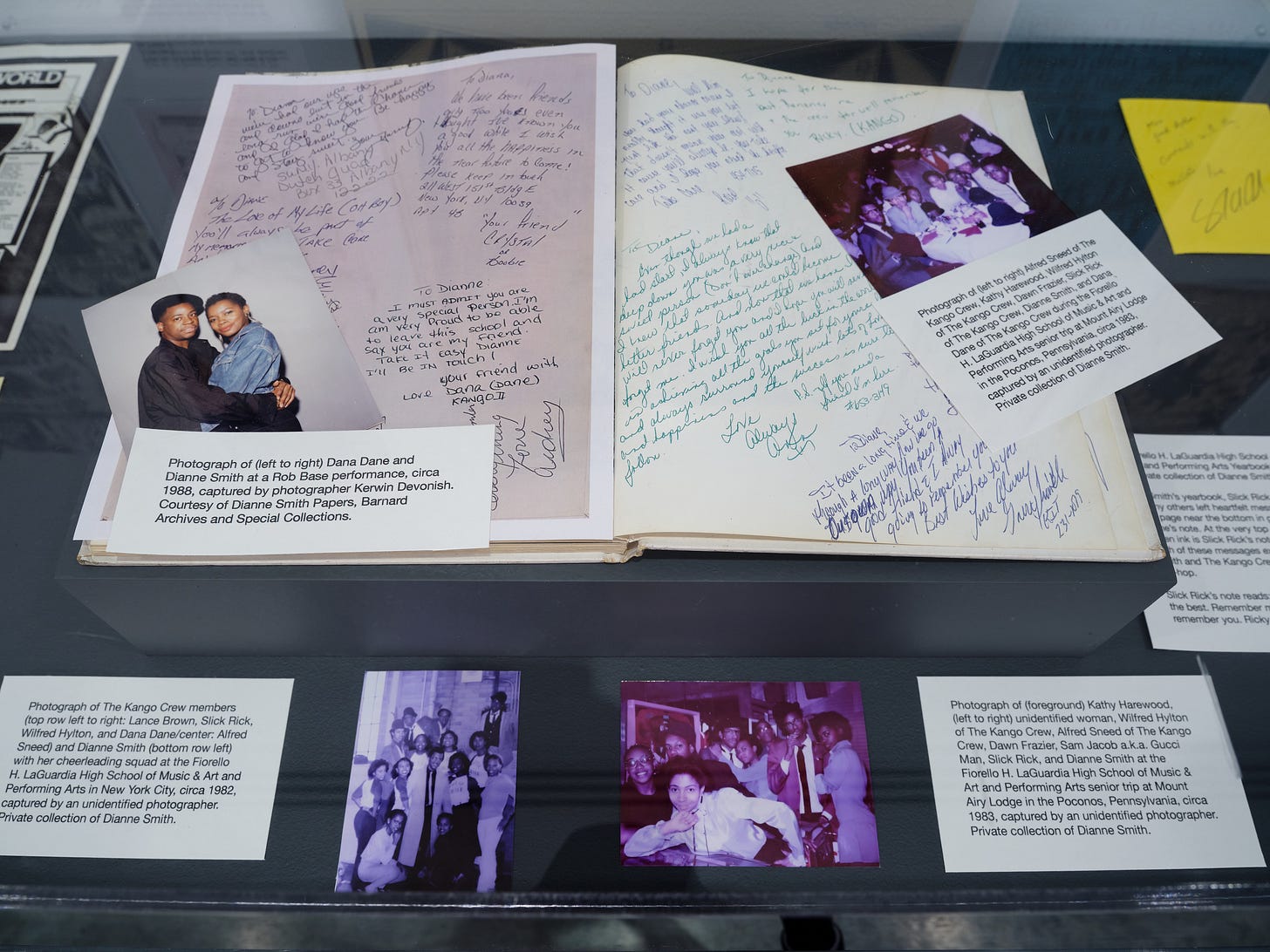

So I am saying, here, look, this is important. I can go to the Schomburg Center and access materials, and then those materials are combined with my lived experience. And there's another level of not just validation but representation. That is real. And the same with the Bronx Museum exhibition. We had the archival materials, but then I had my own that I could go and pull, like my yearbook from LaGuardia High School Music & Art, where Dana Dane and Slick Rick signed my yearbook! And where the Kangol Crew, all of them were my friends and we hung out. There were photos, and there were things that I could draw from that made this project less impersonal but more of a personal and meaningful journey.

Leonardo Bravo:

I love how you're saying that the personal becomes a blueprint for representation, for uplift, and for giving us a sense of a roadmap. I wanted to hear about what drew you both individually to work in the arts, some of your own inspirations, either through your upbringing, family, education, and these touch points.

Dianne Smith:

I grew up in the South Bronx. When I run into people now that I grew up with on 178 Street and Arthur Avenue, and they find out I'm an artist, they're like, oh, it makes sense. They remember how I was really meticulous about coloring in my coloring book. Even back then, I knew that representation was important because I found the brownest crayon to color with <laugh>. If it was Snow White, she was brown. I always colored everything brown. It just made sense to me because everyone I was around looked like me.

Dianne Smith:

Also, I had a mother who was glamorous. Our nickname for her was Dominique Devereux from Dynasty, Diahnn Carroll because she was a diva and a model herself. So, I had that to emulate; her sense of aesthetics, her beauty. She was very meticulous in our household of how things looked. I remember she painted one wall red, and then we had this burnt orange couch sitting in front of it and this huge ornate credenza. So aesthetics were always important, not so much from an artist's perspective, but an understanding of beauty. Coming from Belize a Caribbean culture where you think about the aesthetic of carnival, the Jankunu dancers, and the Garifuna people, that keen sense of aesthetic was always there!

Dianne Smith:

Also, Ms. Jacobs, my middle school art teacher, encouraged me to try auditioning for specialized art high schools. And I was like, okay. I didn't know much, and my parents, being immigrants, didn't understand a lot about the school system, but I ended up at Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School for Art & Music. After that, I applied to an art school, Otis Parsons, in California, now Otis College of Art and Design. I don't know how that happened, but I only applied to one school, and I got in, but ultimately I had a challenging time there, and I didn't understand why until much later. So I ended up leaving and went into fashion, traveled, and one day, I was living in LA at the time after moving back from Europe, and for the first time, I saw something on TV about the Harlem Renaissance.

Dianne Smith:

Now, remember I went to LaGuardia High School of Music and Art, which was on Convent Ave at the time, but no-one ever told me that The Studio Museum in Harlem was just down the street. Wow. So I watched this documentary, and they were talking about Lois Mailou Jones and Zora Neale Hurston and Augusta Savage, and I mean, I was like, oh my God, I'm moving to Harlem to be an artist! So naive. I was married at the time, but I packed my stuff, moved back to New York, figured out how to get myself to Harlem, found my first apartment and the rest is history, as they say.

Leonardo Bravo:

How about your inspirations Souleo? I also want to tell you that you have such an incredible sense of aesthetics. Just the way you carry yourself, what you wear, and your sense of style as well.

Souleo:

Thank you!

Souleo:

So, you know, growing up it was a total opposite experience. I was not into going to museums or visual art. I remember going on school trips and it was like the most boring thing for me to do, <laugh>. And when I think about it, part of it was because I wasn't seeing work that spoke to me. And even in the medium, I wasn't seeing what I gravitate to which is people who work with found objects and, you know, we like to transform them. That's like an amazing thing to me. So it wasn't till much later with my brother, with his passing. Then when I met my partner, Beau McCall, these were two artists that I had around me and they inspired me to want to become a curator.

Souleo:

I had no idea of what being a curator was or meant. Lisa Hayes at Striver Gardens Gallery gave me my first opportunity to curate, we co-curated Emerge. And, Danny Simmons didn't know me from anything and he was willing to participate. And, you know, he's a legendary artist. And this is my first show. So that intergenerational support was really profound for me when I first started, and I'm grateful for that. And also Jacqueline Orange from Art Crawl Harlem and she was part of giving me that first opportunity. So for me as I went along, I've sort of been learning as I've gone along. And what really sticks out to me is really amplifying those sort of underrepresented artists and stories. And in terms of just my aesthetics, I guess I've always been into style as another form of expression and so for me, it's just, it's fun, <laugh>. It's fun to just express myself!

Dianne Smith:

I think what Souleo is saying about the intergenerational supporters really matters because one of the things that was really important for me when I first came on the scene was that I didn't know what I was doing. I was a mess. But I ended up meeting Danny Simmons, who was instrumental in taking me places. This was also at a time when New York looked very different in terms of the art scene; the early nineties when Rush Gallery was around, UFA Gallery, and a couple of other black galleries were around. There was an intergenerational interconnectedness in terms of artists. You would go to Rush, and you would see Gordon Parks, you would see Ed Clark, you would see Richard Mayhew, and I would show with those artists. I was young, but there wasn't a lot of spaces for us to show, so they were mixing generations. So, I would show with Samella Lewis, I would show with Elizabeth Catlett, and such. Someone just sent a picture the other day with me, but it was Robert Blackburn, Jack Whitten, Danny Simmons, Ed Clark, and others, and then there was me! Looking at that now, it's like, how lucky was I to stumble into this world in this way? So again, really lucky and fortunate space I landed in because of this kind of intergenerational interconnectedness that was happening at the time.

Leonardo Bravo:

That is great to hear about this period of history and how much it can inform the current moment. I wanted to get your take on what the current state of representation in the art world of more marginalized voices and perspectives, particularly more expansive ecosystems surrounding black identity, black culture, black aesthetics in the art world. How how do you see that now and how it's grown?

Dianne Smith:

Well that's a really interesting and nuanced topic.

Dianne Smith:

While I think it's important, and I think globalization also has a lot to do with the way people see artists of color, and of course, artists of color have always made space outside of the US. Such as Europe, Ed Clark working in Paris, for example, but at the same time, I think we’re also at a time where the optics are one thing, but we have to be clear: there are still gatekeepers.

Dianne Smith:

And so while the optics are that black artists are thriving because of social media and what you see skews your optics, the reality is there's still a ceiling. Right? And, only a few of us can get to a certain level and place within the art world. So, as much as we see things changing, it doesn't always translate because I still go to events where, you know, it's me and maybe Chakaia Booker sitting at a table, and the only other people of color in the room are people that are serving. So, that tells you how much things have really shifted. Black artists are thriving due to the ways in which their work is being produced, shown, and promoted, this is the optics.

Dianne Smith:

That narrative gets pushed, and it doesn't always leave room for new discoveries and new voices. Only a chosen few, unfortunately, make it within the microcosm of black artists. When it comes to the visual arts, particularly those made by people of color, there's the commodification of blackness right now. And some of it distills some of the real good work that's out there because of this tendency for commodification and the art market. I'm challenged by that. And, so all I could do within this conversation is continue to make the best work possible and to do it in a way that's organic and authentic to who I am. And to make sure that when I choose to articulate myself visually, my hand is visible. And, to be consistent, putting up a show like the Bronx Museum, where they’re all of these different kinds of works, but you can see my hand in it.

Dianne Smith:

The three largest paintings in that show, I actually painted in the gallery. Then, there were the five paintings that I collaged in the gallery. I respond to space and place and because of that, I was like, somethings need to change, something else needs to happen. And then I changed the photographs from Guayaquil, Ecuador, Berlin, and 42nd Street, and then the installation on the back wall was something that was added the day before <laugh>.

Leonardo Bravo:

That's where the curator comes in - becomes guide, becomes coach, becomes manager!

Dianne Smith:

Right. And I’m not the type; well, I’m not an emotional artist, and I'm not a worrying type. How I move through things is like, I don't fail, failure is not an option. So, whatever I need to do between this time and that time, I will! I think that installation happened around two o'clock on Thursday and the show was opening on Friday evening! So I was like, there's gonna be an installation between now and six o'clock.

Souleo:

I was like, she was still installing and I gotta go home and change for the opening tonight!!

Leonardo Bravo:

Oh, that's funny!

Leonardo Bravo:

Finally I wanted to ask what is inspiring the both of you right now? What's coming up for you?

Dianne Smith:

What I am excited about right now is my recent trip to Thailand.

Dianne Smith:

I went with the sculptor Chakaia Booker, who is one of my best friends, she was showing in the Thailand Biennale; this is their third year. The experience was phenomenal, and the level of artistry I experienced was really just beautiful. To be exposed to a whole new world of artists that I would not have known was also really beautiful. It was an international body of 50 artists, mostly Asian, and the level of craftsmanship, dedication, and commitment to the work was really beautiful to see. What I could appreciate about a lot of the work that really resonated with me as a person of Caribbean descent was seeing how their historical contextual information was transformed into this contemporary space. Their identities, their cultural identities, were very wrapped up in how they were making work. So it was really beautiful to see other cultures, particularly from the Asian diaspora, working in these traditional ways with non-traditional approaches. It was very different than going to Art Basel, I would even say the work I saw in Thailand rivaled some of the work I saw at the Venice Biennale. There was a level of ingenuity and creativity that was really impressive, and I was really inspired by that.

Leonardo Bravo:

And Souleo how about yourself? What inspiring you and what are you excited about coming up?

Souleo:

I'm inspired by just the conversations that people are having, like reflecting back on the Bronx Museum exhibition and just thinking about the level of engagement we have with the community, and just reflecting on what they said about how the work impacted them and moved them, made them smile. That inspires me. That always keeps me excited for the next project, the next opportunity. So I find that to be one of my sources of inspiration as an evergreen source of inspiration.

Leonardo Bravo:

That's beautiful.

Souleo:

We're also excited to as Dianne said, to continue to work with her and really outside of just being a curator there's also a consultant angle in terms of helping get her works into institutions, into permanent collections. That's something I'm really excited to continue because I think her work is amazing and I want her to be in these institutions. For example the National Museum of Women in the Arts just reopened with one of her photographs from the collection on display too. So that's exciting because a lot of the artists, that Dianne were mentioning, they've been unsung and now everyone wants to grab their art. I want her and I want other artists around me to be able to experience that now, you know? Yes.

Dianne Smith:

And then, for me, what's up next? I'll be working on a libretto and doing costumes and set design, I'm excited about that at Colby College in 2025.

Leonardo Bravo:

Well this has been such a treat. I'm so inspired by you both individually and the synergy between the both of you. I find that incredibly inspiring. So this was such a great opportunity to connect a little bit deeper and I hope we can continue the conversation.

Dianne Smith:

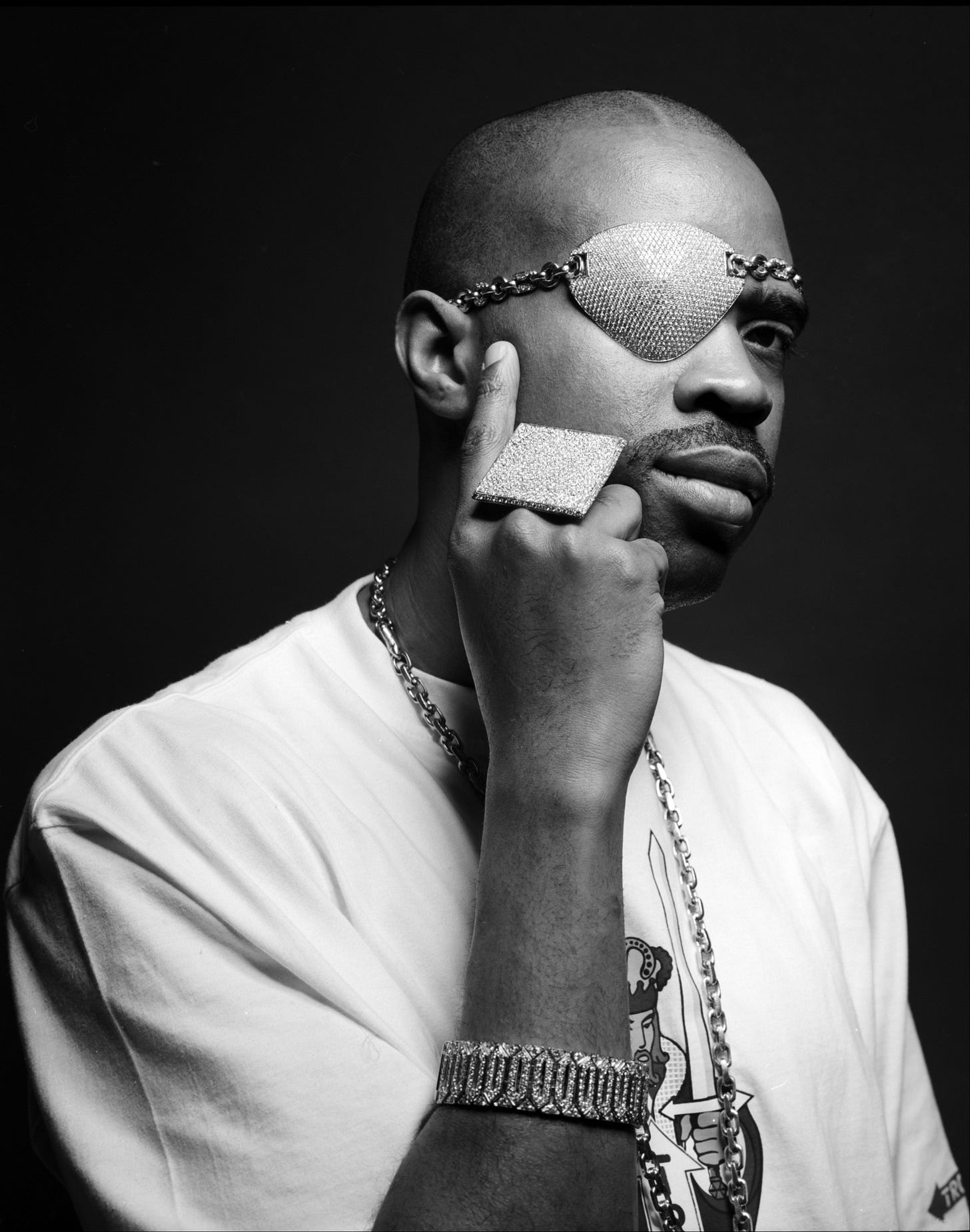

Absolutely. Before we go, I wanna mention we didn't talk about this, but I just want to make sure that I say this, Slick Rick was one of my childhood friends. When we talk about the community aspect and what this all meant, it's important to note that he took time out of his schedule to come to the opening night reception at the Bronx Museum. He did a mini-concert for the community, that, for folks, was just amazing. Slick Rick taking the time to be in the community was significant because he's such a legend within the culture. So I just wanna make sure that that's written.

Leonardo Bravo:

Written and stamped!

Dianne Smith:

I cried because it was like a full circle moment for us, him and I and the rest of us all being in the lunchroom or the auditorium in the morning at like 15, 16-year-old kids with them banging on the tables and chairs creating raps. To fast-forward all these decades later and for us to still be friends, have our voices in creative spaces and relevancy was really special. The fact that we're both from the Bronx, was at the Bronx Museum and again at an institution where there was a time when people who look like us could not hold space in such institutions, let alone one in the Bronx.

Leonardo Bravo:

It also speaks to the perseverance of community and the resonance of these lived histories. I'm so keenly attuned to this notion of how culture kind of permeates and finds those cracks on the street, on the walls, for things to take hold and blossom in ways that we can't even imagine. And I think hip-hop is truly a testament to that.

Dianne Smith:

Right. I mean, one of my favorite things to say is that art is the epoxy that holds a culture together.

Leonardo Bravo:

We'll end with that. That's beautiful right there.