Leonardo Bravo:

Hello this is Leonardo Bravo, and I'm here with Brittany Nelson. Brittany it's great to be in conversation with you as part of the Kaleidoscopic Projects series. For me it's an great way to connect with a broad community of practitioners and people that are reimagining or repositioning our sense of what we can be and how we can define ourselves in more expansive ways. As I mentioned to you that's something that really touched me about your work. I'm always existing in the spaces of the in-between, being an immigrant, being a person of color, having a fluid sense of identity and going through all the struggles and challenges, but also finding those spaces, those gaps or possibilities, which are super powerful. And your work spoke to me about that sense of dimensionality. So that's why I wanted to have this conversation with you.

Brittany Nelson:

Thank you so much. That's an incredible compliment.

Leonardo Bravo:

So I would love to have a broader overview of your practice and how you define it.

Brittany Nelson:

I would say I largely work with 19th century antiquated photography processes which is how my practice started and my research has now landed into the arena of science fiction and space exploration. And thinking about the parallels between loneliness, isolation, in my personal experience, growing up closeted in Montana, in a very isolated and very gay unfriendly city.

Leonardo Bravo:

Bozeman? It's the one place in Montana that I know.

Brittany Nelson:

Bozeman's actually very hospitable. I grew up in a place called Great Falls, Montana, and I remember that the New York Times ran an article, I think it must have been like seven or eight years ago, that said it was the most isolated city in America in terms of a city over 50,000 people in geographic terms, and also the most gay unfriendly place. Which was very validating for me to see that in print and say, oh, that's why I felt that way. Okay. <laugh>. Yeah.

Brittany Nelson:

I research a science fiction author who wrote under a male pen name in the 1970s to get published, but also to express her like very closeted sexuality through not so veiled metaphors of alien encounters. She wrote under the name James Tiptree Jr and her real name was Alice B. Sheldon. I've been working pretty extensively with her archive and lately a specific archive of letters she wrote to famed author Ursula K Le Guin. Ursula believed she was writing to a man named James for eight years. I have the full archive of their letters, specifically I wanted the letters before Alice got outed. I believe it's over 550 page digitized PDF, 550 pieces of correspondence over eight years between the two of them. And it was very flirtatious. It's clear that Tiptree Jr. slash Alice was in love with Le Guin. Le Guin very much enjoyed flirting with James, and they had a multi-layered connection. Previously, I've made artworks with Tiptree's personal notes, and more directly, I have also used the pages of her stories.

Brittany Nelson:

The other side of that endeavor, simultaneously, is working with images from the Mars Rover Opportunity which was sent to Mars in 2004 with a twin Rover named Spirit. They were only supposed to live for 90 Sols. A Martian Sol, or one Martian day, is about 40 minutes longer than an Earth Day. So they're supposed to live approximately three months, and Opportunity ends up living for 15 years. The public heavily personified this robot. Her twin had died seven years previously and here she is wandering the planet alone. What's really interesting is the engineering of the robot was meant to mimic human perception in certain ways where the mast camera, this is one of four different cameras on the rover, but the mast camera that's taking these landscapes, has 2020 vision.

Brittany Nelson:

So there's these two small cameras on the front, they look like eyes. The robot was also built to stand 5 feet tall, which is my height, so these photographs are very much from a human perspective. I view this rover and Alice Sheldon/Tiptree as the same lonely figure. I started reading Tiptree and looking at images from this rover around the same time and I couldn't separate the two anymore.

Leonardo Bravo:

How did you stumble upon or find this duality of Alice and James and open up that portal? Was that by chance or just your interest in science fiction?

Brittany Nelson:

I think what happened was I read a short story called "And I Awoke and Found Me Here on the Cold Hills’ Side." It's quite the title isn't it?

Leonardo Bravo:

Truly.

Brittany Nelson:

The title is reference to a Keats' poem, “La Belle Dame sans Merci” which describes a knight who gets sexed up by a fairy woman and left deserted on the “cold hills’ side” distraught and wondering what just happened to him. Tiptree rewrites this story similarly, but instead a young reporter goes to a space port and talks with the captain. The captain is saying that all the people at the port have become very sexually obsessed with aliens who routinely reject them. The crew members have become addicted to them like heroin. The captain is warning the kid to get out while he still can. I finished this story and said, this is the gayest thing I've ever read! Who wrote this?! And then I was very pleasantly surprised to start to dig into Tiptree and the entire biography. So Tiptree, I would say, was my gateway drug into science fiction.

Leonardo Bravo:

Can you share about the photographic processes that you use, because I think they seem fairly interesting. In terms of the development or the alchemy you use in the dark room, right?

Brittany Nelson:

Yes, very much so. I'm mostly interested in processes where, as you mentioned, there’s a conversion taking place, much like alchemy, where you're converting metals into other forms. Sometimes it's silver halide crystals into solid silver or other transitions that happen that make things either more stable or more unstable in archival terms. And I really desire to work with processes where metals are involved in the direct capture of light. Not the digital sensor that involves layers of interpretation from binary to screen to print, but this more direct form of capture. In this way, these processes are very sci-fi to me —it’s what we’ve determined in pop culture what an alien artifact looks like. It's almost always a metallic, geometric object, with a shiny surface. I found that there's both historically important and entirely experimental and not historically important photographic processes that fit this description with enormous potential, and just haven't been altered or poked at much yet.

Brittany Nelson:

Which also made me realize that in general, photography and photographic history is very conservative. For instance, I worked with tintype for several years with a grant from the Creative Capital Foundation. It was very interesting because largely the practice of tintype photography has been about the perpetuation of tradition for tradition's sake. It's about doing these photographic plates a very specific way, which is ultimately to not cause any interruption on the surface of the plate. The end goal is a clear, uninterrupted portrait of a sitter. For me, it's about ignoring the manual about how to make a tintype because it assumes the ultimate goal is accurate representation — recreating, as closely as you can, human vision.

Leonardo Bravo:

And they probably reflect the standard binary object/subject relationships, the way the male gaze frame and reinforces this. The white male gaze for the most part.

Brittany Nelson:

Absolutely. I mean, the tintype especially as a Civil war era photographic process. This is a very fraught history, and when we look at people who are self-described master tintypists, we often see a lot of overlap with a conservative ideology or a fetishization of history such as civil war reenactments. This is my experience anyways in my attempts to reach out to a network of other tintypists in the South. But thankfully, and more rarely, there is important work being done from artists like Myra Green, who is creating beautiful self-portraits that reflect on race and this fraught relationship with American and photographic history.

Leonardo Bravo:

I want to learn about your influences along the way. Either through family upbringing, education, or mentors that kind of propelled you and influenced you.

Brittany Nelson:

Yes. I had two amazing, strong women as my mentors, one being at at Montana State. I was a first generation college student, so I had to attend state school for the tuition break. It was a fortuitous coincidence that a woman named Christina Z. Anderson teaches there. She has written many books on alternative and experimental photo processes. Her brain is a catalog of photographic chemistry formulas. I learned all of these chemistry-heavy processes, and I thought this was what a standard photographic education looked like. Chris Anderson handed me all the tools I would ever need.

After Montana State, I got accepted to the Cranbrook Academy of Art to study with Liz Cohen. Liz was, and continues to be, extremely influential to me. She gave me the conceptual backing in my art education that opened everything up for me. She taught me how to think critically. How to think big. How to succeed as an artist. These two women combined are really indicative of my practice.

Leonardo Bravo:

Let's talk about the Meet Me at Infinity project and a couple of the key works.

Brittany Nelson:

Sure. Meet Me at Infinity was an installation of a show I did at Fotogalleriet in Oslo, Norway. It's the oldest photo specific institution in Scandinavia. They interest me because they're very conceptual in their programming. The director Antonio Cataldo, who is fantastic, is looking to expand lens based work far beyond its boundaries. The title, Meet Me At Infinity, comes from a collection of short stories by Tiptree that were collected and published posthumously. In the exhibition we had three main components. The Mars rover Opportunity images, these really lonely desolate landscapes, some with the rover looking back at her own tracks.

Leonardo Bravo:

Wow. So poetic.

Brittany Nelson:

These are my favorite, the most romantic. Opportunity is also the robot that has traveled the furthest of any off-planet vehicle. She made it an extraordinary distance. I love the idea that the mission was supposed to be for three months, and then she made this crew stay on for 15 years, in unscheduled missions, doing her very butch science experiments looking at rocks and going where no one has gone, or even seen before.

Leonardo Bravo:

Just looking and searching for companionship. It might be out there..

Brittany Nelson:

Yeah. When you look at the rover images, it's not so unfamiliar. It could easily be from Earth. In the show there are several of these big landscapes, made in a process called Bromoil which is a pictorial-era process circa 1920s. The whole point of this process was to make photography look like painting so it would be considered an art form, and a lot of the bromoils from that era were landscapes. So I was thinking about taking these images from the rover that were being shared on these techno-fetishy space blogs, and very hard science sites, and to put them in this romantic language and to try to force them to have another viewpoint.

Brittany Nelson:

When I look at these images, I see something really different than I think the way that they're being shared or presented online. So they're these large-scale images made from this combination of photographic processes and lithographic inks being manipulated. It's very handmade. My finger prints are all over them. They're very handled. And so we had some of these landscapes in the show, and then a room of holograms. I made a series of six glass plate reflective holograms.

Leonardo Bravo:

I just have to tell you in looking at the images on the website, these works are just stunning!

Brittany Nelson:

Thank you.

Brittany Nelson:

Sometime I'll have to tell you a story of how these got made because it's like completely absurd, but the holograms were a series of handwritten letters from Tiptree. They were not meant to be published. They were just scribbled, seemingly in haste. She was on a lot of speed because of her time in the Army, she also worked for the CIA for a time, and the story gets weirder from there… So there was a mention of these six letters, six pages, in Tiptree's biography written by a brilliant woman named Julie Phillips, who's based out of Amsterdam and she's also writing Le Guin's biography right now. She mentions seeing in the Tiptree letter archive these letters that detail all of the women that rejected Alice/Tiptree in her lifetime. And she called it “Tiptree’s Dead Birds”, and it's a roadmap of why she stayed closeted — in addition to being stuck in the decades and political situations she was born in. For instance, one of the first women she was interested in or tried to make a move on, ended up collapsing in front of her and died of a septic abortion. If that doesn't keep you in the closet. I don't know what does.

Brittany Nelson:

I immediately thought, I have to have these letters. We weren't able to find the originals, which is a long story, but Julie had scans of them. So I took the digital form and ended up making them into reflective holograms as sort of the replacement of the original. I was also hoping in holographic form they would feel like they're trapped in an alternate dimension. The holographic effect I produced is quite simple, it feels like they're floating a little bit off the table. Holograms have something called playback, which describes the 3D effect. This is heightened when you light them from the same angle the laser was positioned to expose them. When you look at the hologram from the side, you can actually see behind the letter. There was a room of these red glowing letters. The third element of the exhibition is this image, it was a brand new piece, but it's this famous image of the face on Mars.

Leonardo Bravo:

Yes!

Brittany Nelson:

It's so great. It was taken by the Viking One Orbiter in I believe 1976 so imagine the resolution on this. It's just a rock, but of course at super low resolution and in the right light, it resembled a human face and everyone freaked out. Not everybody, but it's still a conspiracy theory. And there's even a Hollywood film based on this, it’s called Mission to Mars. It stars Don Cheadle.

Brittany Nelson:

So I've been really interested in this image lately. I had rephotographed the Face on Mars with a very high speed film and developed it in a special way so the silver grains of the film clumped together. It looks like it's made out of sand, so it looks even like more temporary. We put this image up in the exhibition and we built a wall in front of it, and there's a very thin cut in the wall. You can see the image, but you cannot get close to it. It created this very literal distance. We had these weird sized openings in the walls cut in two places at the exhibition, and we put red lights back there. So there were two rooms in the exhibition that were glowing red.

Leonardo Bravo:

Amazing. It's fascinating to hear this. Again how you find the cracks or glitches in the narrative of this person, the slippery construct of identity first of all of this writer and then everything you're kind of building around it, and then this confluence around desire, longing, you know, represented by the rover. And as we're talking, of course that makes so much sense within the construct of working in the arts and having that space to explore these intersections and bringing these points together. Have you had conversations with people in the sciences, perhaps people in NASA that are kind of looking at all this from their own presumably more linear perspective?

Brittany Nelson:

I'm so glad you asked this because this has been a big part of my life recently. I have an artist residency with the SETI Institute. I just did a panel with them at South by Southwest about potentially habitable worlds. I've been in contact with a lot of SETI astronomers and I've been having the best conversations because essentially their proposals for these projects are science fiction stories. I would define science as a thought experiment about a social paradigm or a technology or a conflict and taking it to its logical conclusion, projecting into the future, but it’s important that there is a logic to it.

Brittany Nelson:

So what these researchers are thinking about is how to detect alien signals or where is the most plausible place to look in something so vast as the Universe. You have to narrow it down somehow. And what they do is they tell themselves science fiction stories. They are beautiful and really elegant solutions to a very complex problem. And so I I've been interrogating, that’s probably an appropriate word, <laugh> all of these really amazing scientists about how, what they're thinking about and how they're making this work. In talking about linear perspective, I talked to a colleague of mine at the University of Richmond, his name is Dr. Jack Single, and he's an astrophysicist. I wanted to talk with him before I did this panel. And, and he's not interested in science fiction at all.

Brittany Nelson:

He's not interested in the storytelling and he's very data driven and yeah, it just doesn't enter his mind. So we had a really interesting conversation about is research and after an hour I was really digging at him for something else, and then I said, but what do you do when you're plotting these points on your graph, what do you think about, does your mind wander? Then he said that each point on the graph is representative of an entire galaxy. And probability wise, there's thousands of intelligent civilizations in that galaxy. And he believes this because the numbers are just so strong to suggest it. But if there's an interruption in that data, if it’s corrupted or unusable, he has to throw out that data point. He told me he has this image in his mind every time that he is just throwing away thousands of civilizations, and perhaps someone is doing the same thing to us. I love this idea. And then I said, can I have your trash can?

Leonardo Bravo:

And turn that into poetry <laughs>?

Brittany Nelson:

It's so great. It's just so wonderful.

Leonardo Bravo:

Also let's talk about I Wish I Had a Dark Sea. If you could share with us a little bit on that project.

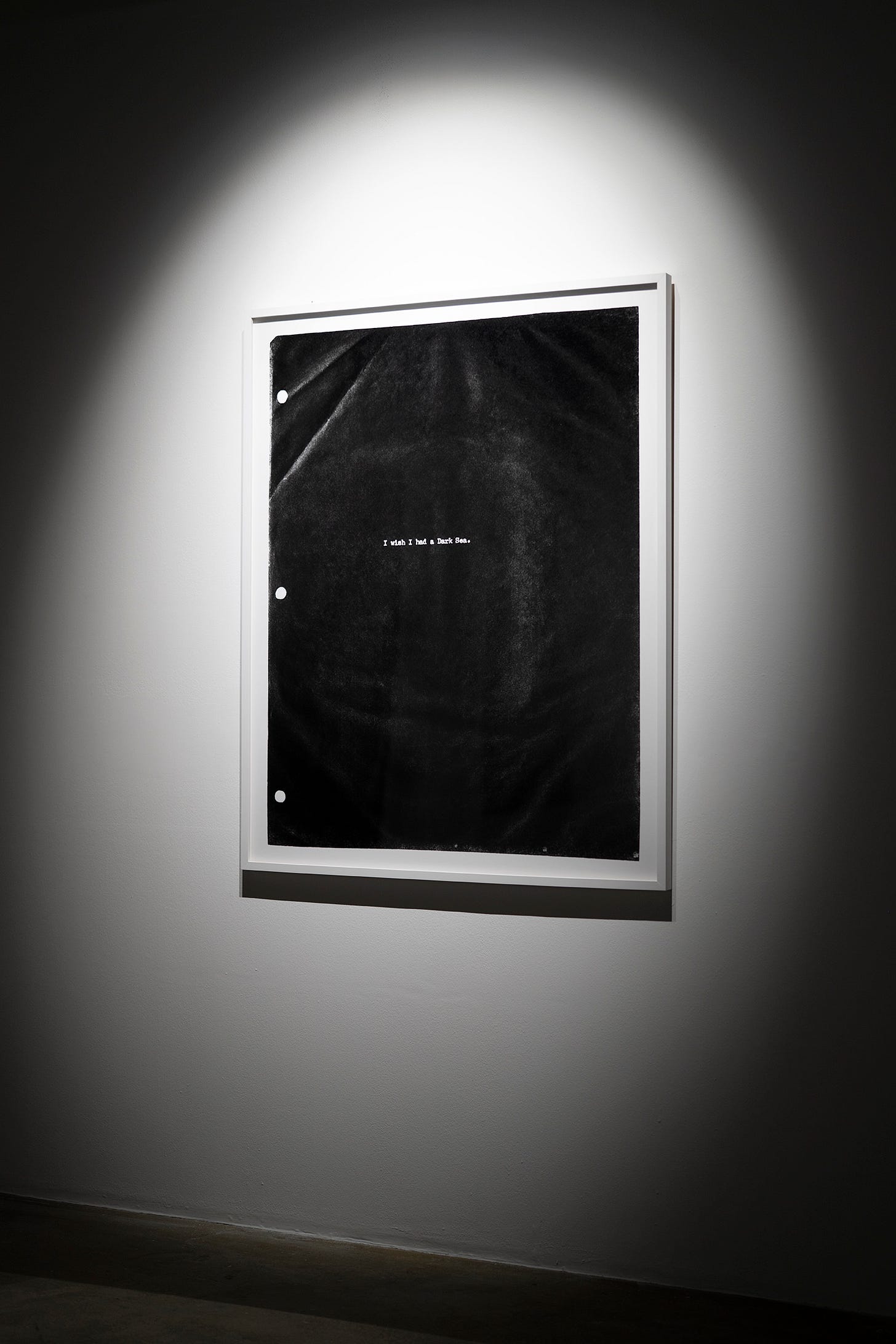

Brittany Nelson:

Oh, sure. I Wish I Had a Dark Sea is from the archive of letters from Tiptree to Le Guin. I've been making some work that is more or less directly from some of these letters. I Wish I had A Dark Sea is a line that Tiptree wrote to Le Guin. This is the only line she wrote on the page. it’s a reference to a story that Le Guin wrote called “New Atlantis”. It's also a reference to an Emily Dickinson poem and also Tiptree's bouts with depression. I inverted the letter, so its white letters on the dark page, the dark sea, and then increased the scale significantly.

Leonardo Bravo:

That work in particular stood out for me. But yeah, the rest of the show as well.

Brittany Nelson:

There was a second letter in that exhibition where I erased all of the texts Tiptree had written, and she had handwritten in the margin to Le Guin - you always understand.

Leonardo Bravo:

That's beautiful.

Brittany Nelson:

It felt like the rest of the text in the letter didn’t matter. The flirtatious nickname for Le Guin that Tiptree used was Starbear, referencing the Ursa Major constellation. I have this spread sheet of every single instance Tiptree uses Starbear in the 550 page archive. And I've been erasing the body of the letter and leaving the Starbear where it stands. In some of the letters you can feel Tiptree’s anxiety increase with how many times Starbear is repeated on the page or punctuated with question marks.

Brittany Nelson:

The exhibition at Le Cap outside of Lyon, France, included some humongous images that were clouds that the Mars rovers had taken on Mars. We included the clouds, the Tiptree’s Dead Birds holograms, and selections from the letter archive. Another work in the show was the very last image that the Opportunity Rover transmitted, which appears as a landscape, but actually where you see the horizon line, where it gets dark, it's where the robot shuts down and stops transmitting. Which is the moment she dies.

Brittany Nelson:

It looks like this beautiful inter stellar landscape. I also made a video, my first video piece, which contains footage of the Arecibo telescope in Puerto Rico that collapsed in 2020. One of the engineers happened to put a GoPro on the viewing station and caught it going down, the cable snapping and the telescope collapsing in this really low res footage. The video is clips from the telescope collapsing and then these transmissions being received which are lines that Tiptree had written to Le Guin. I reconfigured eight years of quotes into a poem. And then we built this humongous screen that was tilted. So when you're watching the video, it feels like it's gonna fall on you and smash you.

Leonardo Bravo:

We've been talking about how your work investigates issues of perception, isolation, desire in these poetic and complex ways. How does that connect or center around your own personal and or cultural histories? How do you see that percolating from it?

Brittany Nelson:

Oh, yeah, absolutely. I mean, it's very strong. I make jokes about explaining the rover passed by landmarks on Mars that were named after landmarks that exist outside of Great Falls, Montana, and saying, okay, I clearly don't relate to this robot at all. I experienced a pervasive sense of isolation and loneliness, that pervasive loneliness that you feel even with other people and not realizing how uncomfortable you are in a certain situation until you leave it. I'm trying to think of a more succinct way to say this, but when we were talking about Meet Me at Infinity and the writing that was associated with it, I guess what I didn't want to have happen is for someone to conclude that if Tiptree or this robot had a community, then it would've solved all of these problems.

Brittany Nelson:

And of course community is super important, but I'm not so interested in easy solutions. I'm more interested in the complications that arise. Tiptree is not somebody that should be necessarily put on a pedestal. She was a very complicated woman. She died by mercy killing her husband and then shooting herself. Leading up that, her biography is almost unbelievable when you read it. I like sitting in these sort of moments of, you know, intense isolation, but also contemplation, which is what space is right? When you are looking into a humongous vacuum, with anyone who's working in this arena it must be almost impossible not to be an armchair philosopher. Which is why I enjoy talking to these astrophysicists so much. And with science fiction, what's so beautiful about it, is that it externalizes the things that are all internal — what your deepest conflicts and fears are. It makes it a thing you can talk to or you can fight or you can observe.

Leonardo Bravo:

It's interesting. I have shared in the past that I grew up in the south of Chile, which is a very isolated terrain. It's almost like the Pacific Northwest. It's like the inverse geographically in the southern hemisphere. So incredibly rough terrain, landscape, weather, the weather's brutal, you know, intense. And there's a unique quality to it. I mean, you feel the landscape, the landscape is almost visceral and dark in the way you feel it. And you know, I long for that place, that desire for it, that memory of it. It's this poetic construct of the place. And I've gone back a few times and it's not there. I mean, it's there, but it's not what was captured by memory and in my soul from being a child. And like you're saying, that construct of the place, it's almost my preferred space because there's a longing attached to it, and there's a contemplation of it, of the contours of that space that feel right for me.

Brittany Nelson:

That's really interesting. I'm so glad you said this because I tried to describe Montana as it feels really. I have a bad feeling when I'm there because it feels like everything is trying to kill you, the weather and the wildlife, it's so isolated in many areas. I'm most afraid of the people back there. But it feels like the land is so wild, it feels like you shouldn't be there. I feel really differently in the wilderness in other places, it has a very different aura to me. It’s a struggle from time to time. I do not want to go back there and I certainly do not want to live there, but it's also very hard for me to be out of being enveloped in such a enormous wild thing. It's hard to be out of that. It's hard to be in the East Village! Speaking of wild things…

Brittany Nelson:

I do like these stories of astronauts going to explore other planets and these sci-fi stories and things like that, where it's like this cowboy attitude I’m familiar with. But in Tiptree's stories, they’re very feminist and they're not about this new frontier and this idea of conquering and all of this colonizing language that's being used in most sci-fi. They are far more psychological.

Leonardo Bravo:

That's fascinating. Brittany this has been really delightful. It's wonderful for me to have this brief moment to connect and I really appreciate your time. I appreciate the depth of your work, and the depth of how you think about it, and how you express it. So thank you for that. I hope to meet and connect in person at some point.

Brittany Nelson:

That would be so great.

*all images courtesy of the artist

https://brittanynelson.com

Fascinating