Leonardo Bravo:

Hello, today I am interviewing an artist and designer from London, Sarah Boris. Sarah, I was just sharing with you that I was drawn to your work because of its sense of joy, particularly the way you use colors, the way you use forms, and the way your work functions within public and social space. I am currently in Los Angeles and you are in London right now, and I thought to start off with a general framing from your end about your practice, and how you define it.

Sarah Boris:

Hi, Leonardo, thanks so much for having me. I describe myself nowadays as an artist and designer. I've been transitioning throughout my whole journey to various positions (from artist to graphic designer to art director to artist). In the last eight years, I've found myself in moments of redefinition and work transition where I'm reconnecting with the artist in me and my art practice, which I had sidelined in favor of design commissions. Today I'm sharing time between my art and design practice. It's definitely a work in progress, but I would say that my art practice is focused on a lot of different outputs such as concrete poetry, pop art, sculpture, and even to some extent, what I would call functional sculptures. I currently favor paint, wood, screenprinting and colour pencils currently to make my artworks.

Sarah Boris:

Maybe the clearest functional sculpture I've created in recent times has been the heart benches, a sculpture which is also a bench installed in the public space. Currently, I'm working on a couple of wordless publications which I have conceived. I'm also working on a book which looks at language and which, hopefully will be published later this year. It's a series of words which look at correspondences between French and English language. It's an introspection of sorts into how words and spelling functions in my mind and my constant transition from speaking and thinking in both languages.

Leonardo Bravo:

That's interesting about coming into this moment of recognizing or a redefinition of your practice. Much of these conversations with Kaleidoscopic are with practitioners that think about their work in very expansive ways in the sense of how an artist frames and sees the world and how that can be expressed visually. As we're talking it made me think of Sister Corita Kent, who was as you know, a seminal artist here in Los Angeles, very much an activist, a socially politically activist nun at Immaculate Heart College here in Los Angeles. The way she used visual language to promote a sense of social engagement is very relevant to this moment.

There’s facets of your work that kind of resonate alongside that. The combination of being actively present in the world through visual and creative engagement. Were there inspirations or mentors that connected or instilled in you the way you pursue your work?

Sarah Boris:

I think there were definitely a lot of different influences. After a baccalaureate in Arts and Literature, I did a foundation in arts and design, followed by two years of typography in Paris. I then moved to London where I did a Masters degree. I had always been painting a lot, it's always plunged me into a state of being where I felt really happy. I never really liked painting at school because I always felt very paralyzed if someone was watching <laughs>. So I think it's a space where I found myself more at ease on my own.

Sarah Boris:

During the foundation year a teacher advised me to study visual communication although I was initially interested in fine arts and sculpture. We're meant to decide on a speciality very quickly. Although it was not necessarily the pathway I had initially set out for, it has given me a set of ways of making my work and probably finding my identity as an artist today.

Sarah Boris:

A lot of this I only realized after leaving my full-time job in 2015. During my spare time I started doing a lot of pop art works, often with a relationship to text and words. I became interested in mundane things such as fruit labels often with a narrative in mind or forming a typology. For example, there was this Elle & Lui (her & him) which I found incredibly romantic, which I had seen on a little fruit label. And I started wondering why it had such a romantic name. Then I found more and started collecting all the ones that had romantic callings or the ones with names.

So for example, Monica, Pamela, Bruno, or Chérie, and then screen printing them. I would start blowing them up on the photocopier and re-drawing them by hand at a much larger scale. I think there's always been a sort of a counteract with my art practice freeing myself of all the rules I had learned. I am allowing a lot more freedom and detachment when I make artworks. It's very liberating.

Sarah Boris:

I grew up from the age of two to six in the US. During some of that time we lived in front of a candy store! I have quite vivid memories from that time, I remember running off across the street into the candy store which felt a bit like a gingerbread house. I was five, so I didn't have money <laughs> so I mainly just stared at the candy labels (The Fun Dip and all the Willy Wonka factory stuff and the Jolly Ranchers): I was just like someone who would go into a gallery and contemplate paintings. Again, it's only recently that I realized that it might have had such an effect on my sense of color and my love of pop art. I've always been swaying between very minimal artworks and very minimal use of color, and now going back to much more colorful things.

Sarah Boris:

I still think that I'm in a liberation moment where I'm sort of breaking all the rules we're taught at university and finding new ways of expressing myself through my artworks.

Leonardo Bravo:

It's interesting as you're speaking about a liberating sense of your practice, and thinking about these more liberating aspects of it all. Can you share what it's been like to work with some really outstanding cultural institutions in Britain? Some of the visual identity work you've done and the process of working through that and how that's led to your identity as an artist.

Sarah Boris:

I think one of the things that's kept me working in those institutions was (amongst other reasons) the fact that it was like a massive extended learning and playing field for me, being in touch with all art forms from visual arts, film to music.

Sarah Boris:

At the Barbican I worked mainly on rolling out the visual identity that had been in place. I had sort of a hunger as a young practitioner to always do more and to be hands-on. I wanted to try new things and I started being very specific with the projects I wanted to take on. This drive gave me a sense of direction. At the ICA I was commissioned to redesign the visual identity two years after I had started working there. I noticed that everyone felt invested in how the institution was represented visually (exhibiting artists, curators, front of house staff, etc). The main way to approach the redesign was to involve everyone so I organized a series of group discussions inviting all the staff with up to ten participants each time. I ran about 10 of these group discussions.

Sarah Boris:

And I gathered information and that informed the approach for the visual identity. I guess at the time it was also partly informed with the economical context through the output of monochrome printed matter. More importantly I became interested in the ICA's history and the output from the 60s. I dug into the archives from that time. One thing that I loved was how they were approaching their communications and more than the visual aspect, I became interested in the writing found in the printed matter of the time, the use of language. There was something about the writing, which really felt like storytelling and was somehow very inviting.

Sarah Boris:

That really appealed to me: a purity and honesty in the tone. That's why I'm so interested in my artworks with words and or labels or all these pop art references. It's a way for me to bring back this very simple way of communicating but still leave people's imagination open without sort of putting it all out there, I think.

Leonardo Bravo:

Let's talk about some specific projects such as the heart bench. Describe the process and getting to the actual installation of the object.

Sarah Boris:

At the end of 2020 I received a message inviting me to take part in the first edition of a contemporary art festival in France (Les Temps d'Art) in a town called Saumur. I was really keen to create something which would involve a traditional craft from the city and which would allow me to collaborate with local artisans and producers. I felt this was especially important after working in isolation and being homebound during lockdown. My first desire was to reconnect with other makers in order to create my artwork. Originally they wanted me to create a typographic artwork, but I found that with these commissions there is scope to try new mediums. This is something I am keen to do as often as possible to avoid staying in my comfort zone and push my practice further.

Sarah Boris:

Luckily, the people who were running the festival fostered and enabled the ideas I developed which involved working with a stone mason and a local wine maker. They also introduced me to a historian as I was keen to find out more about the city's history and anchor my artwork within a specific context. Throughout further research I found out that the castle had been called the 'Castle of Love'. The series of artworks I created respond both to the naming the Castle of Love and to my personal observation during lockdown that the only spaces where we could sit were actually in parks and on public benches.

Sarah Boris:

The public bench was one of the most sought after during the pandemic as I witnessed in London, living close by to a park which was still accessible during lockdown. I noticed how all park bench designs were very similar. I also felt that a sense of people reclaiming public spaces was very strong and beautiful and that we should perpetuate that by enhancing public spaces post lockdown.

Sarah Boris:

That's how my proposal came about. I was keen to create with materials that were from the city which has a strong history in stone carving with the particularity of so many houses and the castle being built with limestone. They still have a practicing stone mason school in the city! I got in touch with them and proposed the idea of the heart benches, they were up for helping me make them.The benches were installed for the festival and exhibited there, with visitors invited to sit on them, the artwork entering the realm of functional sculpture. It was really fun to see people's interactions with them and also the comments, for example someone said, is this from Alice in Wonderland?

Sarah Boris:

Or quite a lot of people being like, can we sit on this? It's like a sculpture - are we allowed to sit on the sculpture? I decided to paint the wooden beams of the bench in this very vibrant, almost neon like red, giving the sculpture a traditional and a contemporary feel at the same time. Again, as I like to observe people interacting with the work, I stood in the courtyard where they were exhibited without flagging up my presence as the artist and just observed people navigating in between the benches, sitting on them and commenting. And seeing a lot of lovers just sitting on the bench and asking for photos to be taken of them on the bench.

Sarah Boris:

It was also just this sense of injecting a symbol like the heart – that is so universal – back into the public space and seeing that it creates such a level of interaction and joy. That's not something that I ever premeditate or project in any way: how people will react to the work. It's also very hard to anticipate people's reactions. I have been deploying a lot of universal symbols in my work such as the sun, hearts, or at the moment I'm doing several projects deploying a rainbow which I hope to exhibit as soon as I find a gallery. I'm also hoping to make a series of sculptures but the reality of making sculptural works which are very big and very heavy is that you need the space and the framework to make them. The ideal scenario is within the context of a commission.

Leonardo Bravo:

Just wanted to touch on a couple of other projects, LOVE for Ukraine and Subverting the Rainbow, and how this work might reflect or be centered on the social, political, and climate upheavals that we are all facing.

Sarah Boris:

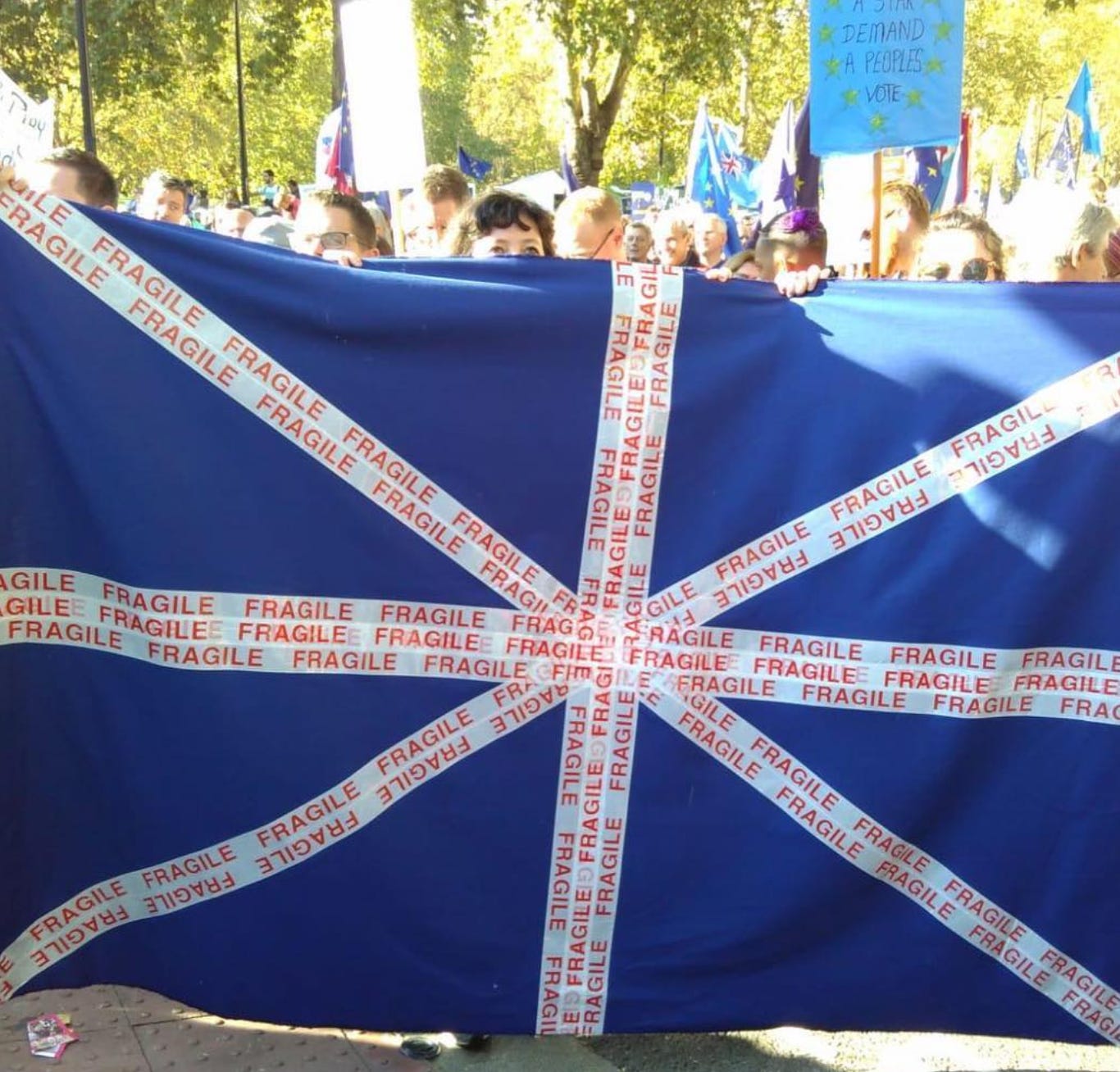

I have created political works that are linked with either the environment or current world news. I created a screen printed edition of a typographic artwork LOVE for which all proceeds were donated to UNICEF Ukraine. To balance some of the political projects, I would say the sculpture of the heart benches or the rainbow artworks are definitely part of what I would call my care bear art phase. Making political artworks is a way of expressing solidarity or how I feel. For example the Fragile UK flag is an artwork that I made in response to changes in the UK such as higher education fees tripling in 2015, the defunding of the healthcare system and the loss of freedom of movement. The flag was a way of communicating how the sense of identity of the country as I'd known it was changing. Interestingly, people are still asking to exhibit it more recently and it's just been released as a screen printed edition by a gallery in London. It was interesting to see that the artwork that I have made in the most DIY way has become one of my most well known pieces. The original version is made of fragile tape applied onto blue paper stock.

Leonardo Bravo:

Yeah. It feels very punk. I mean, visually it reminds of much of the design work Jamie Reid did for Malcom McLaren and the Pistols, so there's kinda like that attitude and immediacy to it. There's simplicity of the action but it embodies so much, certainly a sense of energy and urgency.

Sarah Boris:

That was a bit of a turning point for me in terms of the works I made. And then I made a book, I'll send you one if you want, but it's called Global Warming. Anyone?

Sarah Boris:

It features over 120 tweets by the 45th president of the US on climate change. It's preceded by an introduction by Tommy Walters, who's now a producer for PBS Newshour, he puts it in context in a really interesting way. That project was interesting for me because I was invited to take part in an exhibition called Manmade Disaster, how Patriarchy is Ruining the Planet. This was also a chance for me to respond with a painting or with a big screen painting but interestingly, I went back to the book form, and I think the book form is definitely part of how I like to make artworks and express ideas or commentary. Little did I know that the 45th president of the US would be banned from Twitter shortly after I published the book.

Sarah Boris:

So this became a real piece of archive. For the exhibition, I had only made five copies printed on a material made from recycled paper cups. I felt it was important to choose environmentally sound solutions to make the book. After the exhibition a Green MP at the European Parliament ordered 20 copies of the book. I thought I should do a reprint as I did not have enough copies and release the book.

Sarah Boris:

So I expanded the first edition with new tweets that had appeared on climate change. The expanded edition was then published in an edition of 120 copies which corresponds to the number of tweets it includes. And then I thought, well a book is not completely a book without a book launch and I do like having a dimension of social gathering and events around an art project. And I did a book launch, one in London and one in Paris. I was speaking with a design journalist who's also a DJ, Emily Gosling, I asked her if she would be up for doing the soundtrack for the night of the launch? She gathered apocalyptic music, and played it on the night. Finally I also made these bookmarks showing the twitter bird transferring the digital act of bookmarking a tweet into a physical analog act of bookmarking.

Sarah Boris:

The addition of the bookmark is what I would call a small gesture, but I really like including those details in projects, it's like a pied de nez between the digital and analog worlds. At the end of the book there are three biographies: we have a bio of the journalist, the 45th president and myself.

Sarah Boris:

I created the first iteration of the LOVE typographic artwork during lockdown. When the war started in Ukraine, my sister's family in law who lives there, was directly affected and had to leave their homes.

I had been working with a screen printer called Harvey Lloyd Screens in the UK on several artworks. Together we decided to launch a version of my LOVE artwork in the Ukrainian flag colours. A screen printed edition of 100 was made and sold out quickly. I have a couple of artist's proofs left.

Sarah Boris:

This is how some of these artworks and projects happen. It's through collaboration or sometimes it's through a strong link in my own family story or in this instance, my sister specifically, she was living in Kiev until 2014.

Leonardo Bravo:

The other piece that you mentioned, especially with the book about the tweets, is the kind of life that a project takes on after you create them. The kind of engagement that they have with the public, or the way they touch people, and the way people attach themselves to the work too. That to me is really critical and important because then the work begins to have a different kind of agency in the world as well. I wrote down that you're thinking about a wordless publication. What would that look like?

Sarah Boris:

There's a couple that I'm working on. And one is actually a reprint of the graphic theater which is a wordless book where the sea becomes a theater curtain. It's been out of print since 2016. And when I have something in mind like this, where I just feel like it should keep on living, I really want to reprint it. My ideal scenario would be to find publishers for these projects but they are quite niche. They sit in an artist's book category, but they might not necessarily fit in what you would call a children's or comics book category.

Sarah Boris:

What's been interesting for me as well, because it will be the third edition is the possibility to revisit the book each time. Every edition is printed in a different way (the first was digital printing on Mohawk paper, the second was riso printing on Munken paper). I've also reworked the whole artwork each time. The new edition will be offset, with five Pantones and with the most pages yet. It's also an exercise in style. This wordless book is on the metamorphosis of shapes and how we can establish analogies between shapes and how they can be read differently with a new colour, it's also a comment on climate and rising sea levels

Sarah Boris:

There's a passage in the book where the red starts seeping into the blue waves. And that is also a comment on overfishing. I don't say it explicitly but it is part of the book. Then there's another silent book that, well wordless book, that I'm working on, which looks at color and how colors mix. The book is titled Rainbow. It's a project that I made during lockdown. In the UK, the rainbow became a symbol of hope. It became a subject for workshops at home.

Sarah Boris:

People started posting on their windows drawings of the rainbow. Everyone was also drawing rainbows in support of the NHS / the hospital staff. There was a mass expression of saying thank you with rainbows and it became a symbol that was everywhere during that time.

Sarah Boris:

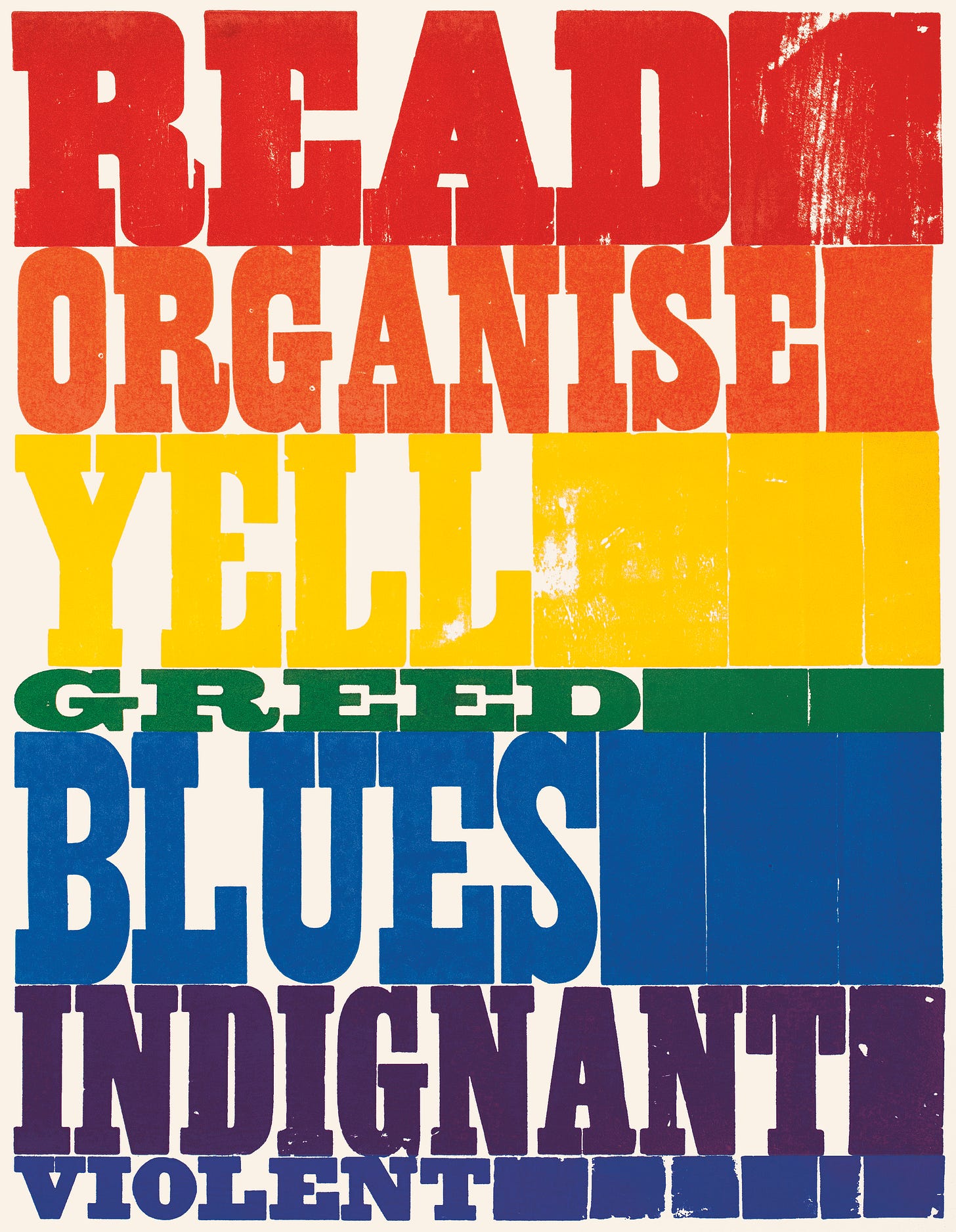

It did transpire through my own work a couple of times and still does now. For example a letterpress artwork which I created titled 'Subverting the Rainbow' printed at New North Press in London, but also the Rainbow book, it's a sequencing of colors, when you arrive at the center spread, the formation of the rainbow is complete. Until you arrive at the center spread you can only see slices of colour. Two limited edition versions of the book, both with different hues are to be released – published by Corners based in Seoul, Korea. There is no printing in this book, so finding the right paper pigments became crucial. It led me to researching many different color papers in existence. I did find a lot of paper makers that had beautiful colors, but I wanted to make sure the sequencing and juxtaposition of the seven colours would be perfect. Sometimes one colour in the sequence would not fit so I kept searching. Finally I settled on Takeo (Japan) which has truly unique and stunning hues.

Leonardo Bravo:

So, Sarah, the final question is always what is inspiring you? What are you admiring, what's given you joy right now, either in your practice, outside of your practice, you know, what's feeding your soul ultimately?

Sarah Boris:

One of the things that's giving me a lot of joy is trying out new things where I'm absolutely novel to them. Stepping away from the computer and not using technology to make new works makes me really happy. I am reconnecting to all things physical, which are moments where I forget time for example. Someone said to me that I have a happy grin on my face when I'm drawing. Collaborating with artisans and a lot of different people in different crafts brings me joy and allows me to learn new things. It also helps me see where I want to take my 'physical practice'. I would definitely say that is my happiest state, both in terms of what I'm learning and also ways of life that are in real opposition to the heavy screen lives a lot of us have. I think the uptake in manual work and craft is very significant as we enter the age of AI. It inspires me to see that there is a sheer desire to not just be in a technology based meta verse world. The act of making and bringing people together, that's really where I want to be.

Leonardo Bravo:

Beautiful! There's so much to this notion of a different relationship to making, to form, to expressing yourself with materials in a way that's far more direct and tactile.

Sarah Boris:

Yeah, I think it's the tactility of it all.I would definitely like to add another thing is that another thing that really inspires me and keeps me excited about the world we live in is actually meeting people like you!

Leonardo Bravo:

Aww!

Sarah Boris:

But it's true, because I think it's just fantastic when someone reaches out like this and connects. I've been reading interviews you've been running and it's really inspiring. So I'm really grateful that you're taking the time to meet with all of us, and I hope we can all gather at some point.

Leonardo Bravo:

Thank you Sarah! That's such a great point because my happiest place is creating opportunities to collaborate and create that setting for people to come together. And I think part of it, of course, over the last few years, it's been much harder. So this project in a way is a way to create a network, create that community in a really broad sense.

Leonardo Bravo:

So yeah this has been a joy and it does feel like a way to extend a community in the world.

Sarah Boris:

Perfect. Thank you so much.

IG: @sarahboris_ldn