Leonardo Bravo:

I'm here with Kaleidoscopic Projects interviewing Chloë Bass. Chloë, you are in New York right now and I'm in LA for a little window of time. I reached out to you because I've been following your practice and am fascinated by the way you approach your work, particularly from my own interest in the built environment, in public and social spaces, how these function and how those spaces begin to give us shape and define identity, and a sense of how we navigate the every day. You offer such a wonderful lens and prism to connect to that.

Chloë Bass:

I love that idea, the way that you state it, that space gives us, or shapes, our sense of identity, because I think that is really strongly true. But I don't think it's something that people talk about enough. And I think we think of identity as being so internally driven, so personal in a way, it's like public and private, right? It's shaped by these private forces, but also, we know, by societal forces. Certainly like issues of race, sex, gender, class, right? Those are all societal forces that impact how we see ourselves. But I also think that space, especially public space and design, have this really strong impact on our bodies that isn't just psychological, but actually tells us in a lot of ways who we are and how we should behave. And whether or not we feel comfortable within those restrictions is a question, right? But like, we think of those discomforts as being, I think, also identity driven, or we talk about them more as being identity driven. In fact, I think they go even deeper than that towards a sense of like, what is it to be human and: what is it to be a human being inside? What is it to be a human being outside? And how is space telling us who we are, regardless of who we are on a more, you know, individualistic level. So yeah, I'm happy to be thinking about that.

Leonardo Bravo:

Yeah, that is profound this notion of, what is it to be human? As I was sharing with you my experiences of the last eight months of being in Berlin and having almost this uncanny experience about place, you know? Especially in a city so deeply affected, troubled, and shaped by a deep history. And then, my comparison of course is Los Angeles where everything's so horizontal and dispersed, it's ephemeral -- things turn over so quickly. So again this deeper question of what is it to be human and what are those stories that tell us who we are as human beings, inside a sense of place and space.

Chloë Bass:

Well, and it's like, what does a changing landscape tell us about what to expect. Right? I'm in New York today, but my work is in LA. I have a show up at the Skirball Cultural Center right now called Wayfinding. Wayfinding is a project that was initially commissioned by the Studio Museum of Harlem in New York to be displayed in New York, specifically in Harlem, and then traveled to St. Louis, Missouri, where it was expanded and presented by the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, and now has made a West Coast stop at the Skirball in LA. And it, you know, I feel like anytime in LA, and I'm in LA quite a lot, I feel like anytime in LA people are like, the weather's been weird. And I'm like, yeah, that seems like it's always weird. It's just always weird in a different direction. But you guys aren't really used to having weird weather because for so long, the whole point of Southern California was like this beautiful —

Leonardo Bravo:

Temperate climate all the time!

Chloë Bass:

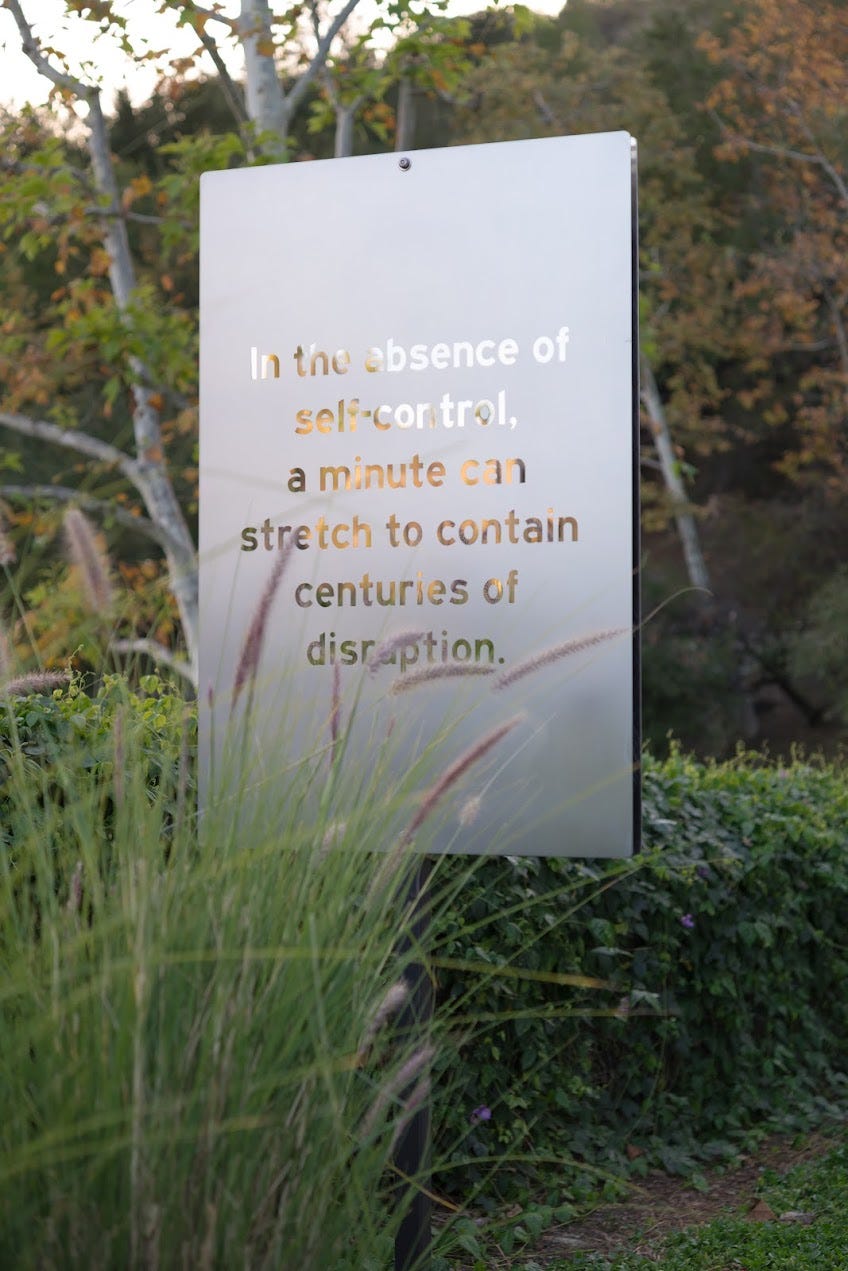

Every day is 75, and it goes down to maybe like 48. Right. And you know, that's your day. Right? And now things have been quite wild. Having work installed on the grounds of a museum, it's a really beautiful environment. The Skirball is out by the Getty Center. It has a kinda similar, hilly, built into the landscape feel. The buildings are designed by Moshe Safdie, so you have this great natural and environmental kind of space coming together with manmade architecture and structure and movement and light and all the southern California stuff. What has happened over the course of the project is that LA has gone from a period of deep drought at the end of the summer to really overly abundant rain and flooding. And that that has happened kind of a few times as the project has been up. And you can see that in the work, right? Not just because it got wet or whatever. It's made to withstand any type of weather. And has, in fact, been through in New York, a hurricane, and in St. Louis the weather gets very hot and also very cold. So I know that it can do all those things, but what you see, because some of the surface is physically materially reflective, is the change of the greens and the other colors in the landscape that emerge and recede as weather patterns shift. And that also is not the built environment, right? That is yes, an element of landscape design. The grounds at the Skirball are extremely carefully and beautifully cultivated, but whether or not it rains is dependent on the weather. And so what you're seeing kind of emerging or disappearing in the work is something that is out of our control, but still in a way, I think tells us, whether you want to call that aesthetically or environmentally, how we are doing and how to be.

Leonardo Bravo:

Can you describe more about the premise of the Wayfinding project? And how the project has changed aesthetically, creatively, conceptually through different sites and stages.

Chloë Bass:

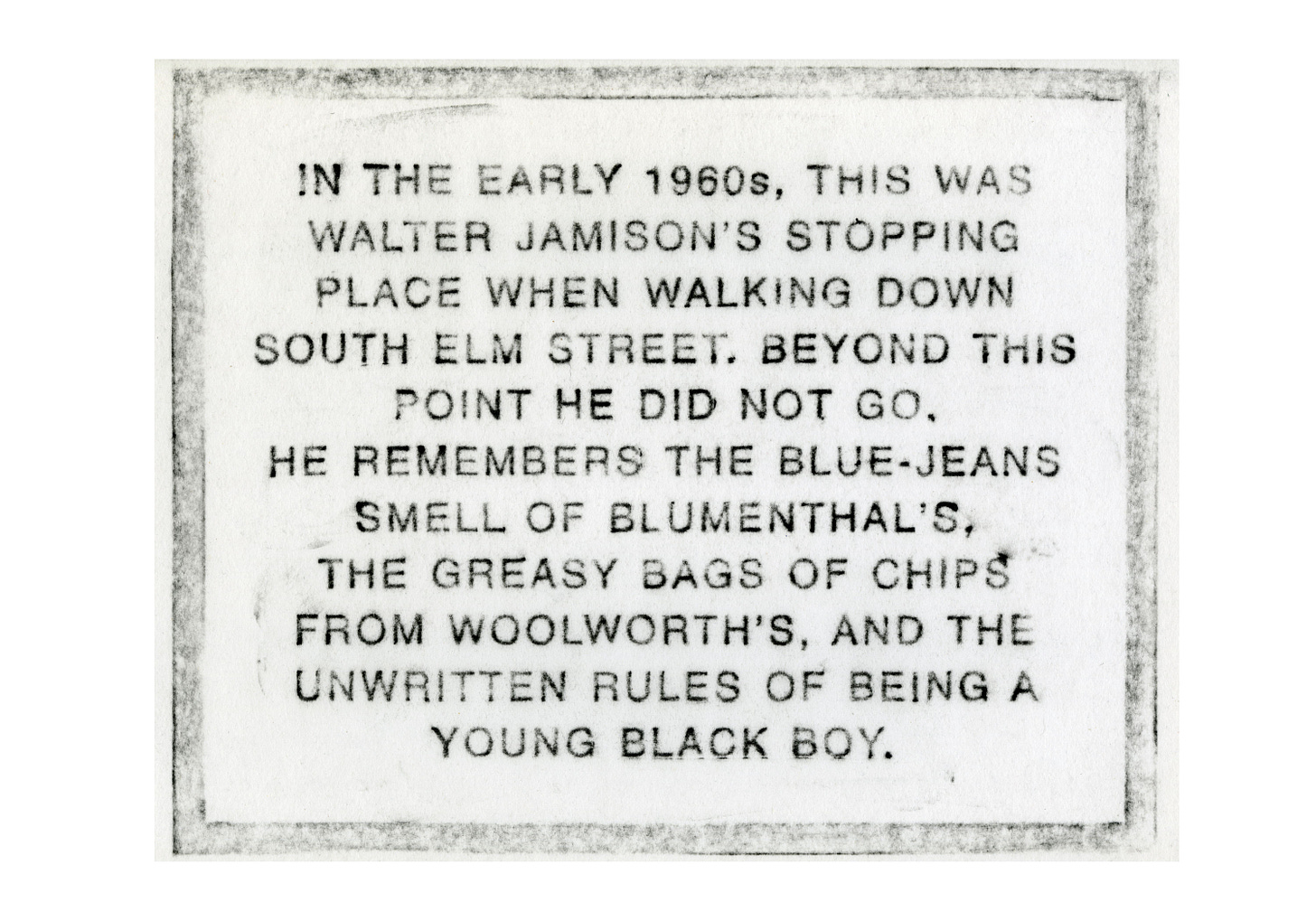

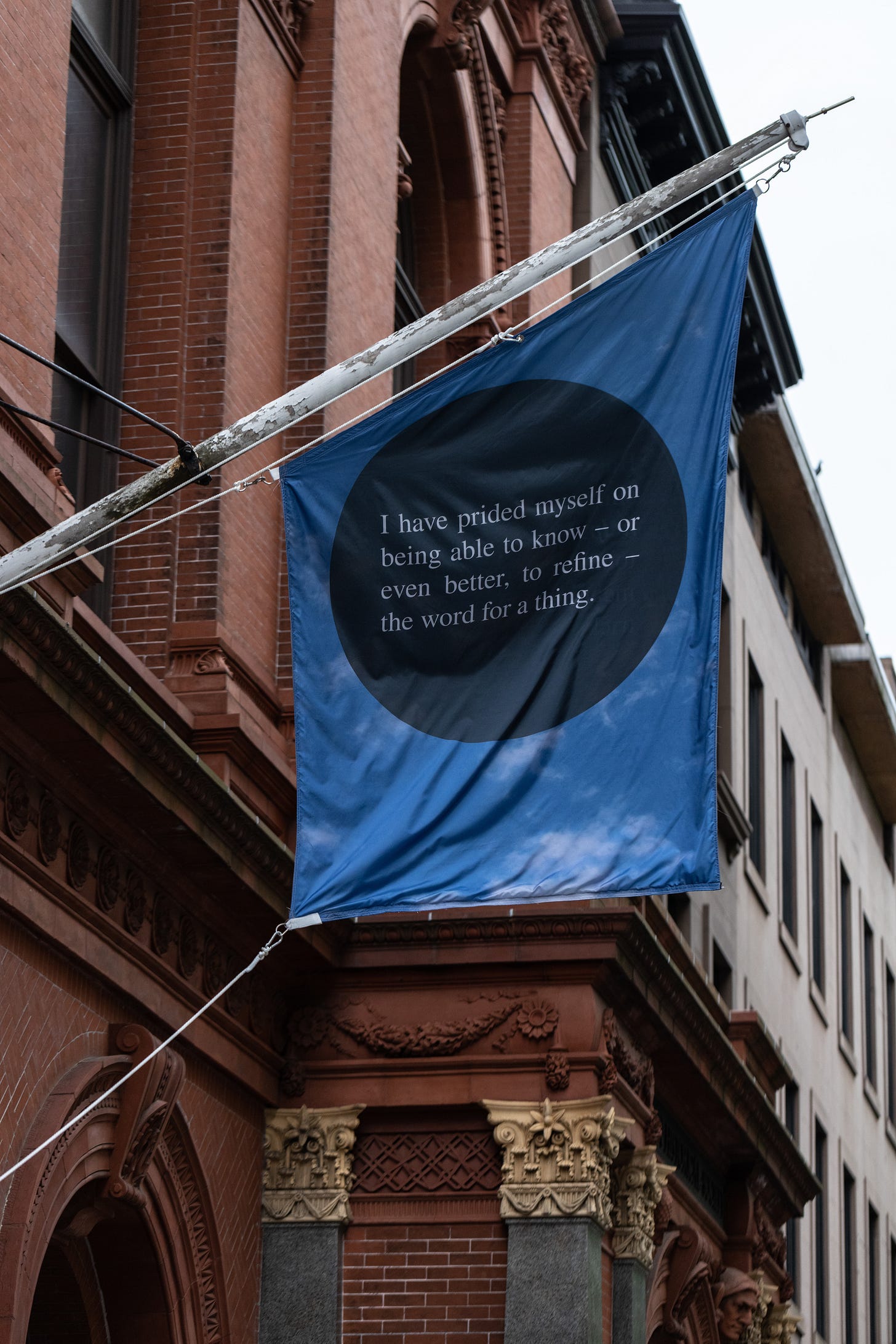

So Wayfinding is a series of sculptural objects that mimic public signage. And they mimic three different scales and four different types of public signage. The three scales are a billboard, which is ten feet by four feet across on the sign face. Then there’s a kind of poster sized sign, like a movie marquee poster, 24 by 36 inches. And that type of sign exists in two different forms. One is as a double-sided thin aluminum that has text on it. And the other is as a clear acrylic with an image printed on it, and through it you can also see the landscape, both above and below and behind that image. And the third scale of sign is a five inch by eight inch garden marker, like you would use in a botanical garden as a tree tag or a plant identification worker.

These different types of signs have different registers of language on them. The billboards each contain one major, kind of central question. The 24 by 36 inch signs that have text on them have iterative sentences that change slightly, and those are double-sided. Each sentence is partnered with another sentence consistently throughout the project, but then those sentences are always subtly changing. And then the smaller tree tag signs, the garden markers, have pieces of basically short personal narrative.

The project, in terms of design, this is an easier question to answer, has not changed since its initial presentation. The only thing that changed is that because of the pandemic, and then because of shipping and material and labor costs, my fabricator in Red Hook, Brooklyn was not the person who made the signs for the later versions. But he actually was really generous in sharing how he made those signs. And so as the project expanded and an additional set was fabricated in St. Louis, they were fabricated to the specifications of my fabricator as best was possible. And then in Los Angeles, there's a further expanded view, so that includes everything that was initially in New York, everything that was added in St. Louis and the new section that was fabricated in LA, also according to the same specifications. I can tell that you to me, they do not look exactly the same.

Leonardo Bravo:

How have you found the public interacted or engaged with the project?

Chloë Bass:

It's been a journey, because initially the project was presented in a public park, right? It was a museum exhibition, but it was not on the grounds of a museum, it was in St. Nicholas Park in Harlem. And so people who were there in St. Nicholas Park were not necessarily coming to the park with the idea of having an art experience, which I think is really great, actually. And I did find that the project got a lot of love and was missed when it was gone. I still sometimes hear from people who live in the area being like, “my memory came up on my phone of your project.” People who I don't know. They'll find me, usually on Instagram, and DM me and be like, “I just had this memory pop up on my phone cuz like, on this day, two or three years ago or whatever, I saw your project.” And it's so beautiful, it's so generous of them to tell me.

But as the project traveled, in St. Louis it was presented by the Pulitzer on their grounds, but their grounds are not roped off in any way, they're not locked, right? You don't have to go through the museum to get to the grounds. So it appears like a public park, or it has the constantly available nature of a public park, but it's actually land that's owned by a private institution. And then now in LA at the Skirball, it is of course only available when the museum is open. So you can't just come through and see the project at any time. So if the institution is open either for regular museum hours, or it's available for an event, cuz they do lots of events there, people are able to walk through the grounds and see the project, but it's functioning in another way, a lot more like a traditional exhibition than it did at either of the other two sites. That said, at neither of the other two sites — well, that's not entirely true. I was going to say at neither of the other two sites did it become also the backdrop for events like people's weddings, but in St. Nicholas Park in Harlem, it did become the backdrop for like incidental events, like children's birthday parties that were being held in the park. You know, I grew up in New York City and when I was a kid, 75 to 80% of my birthday parties were just in Central Park because we lived right there. And I have a summer birthday and it's cheap, and it's right there! So I did get images of the Wayfinding signs when people had tied balloons to them for parties and stuff in Harlem. And I thought that was really lovely too. But now at the Skirball it's more formal.

Leonardo Bravo:

One of the things I responded to on an initial view of the work, is that it belongs within the textures of the everyday. It belongs with the textures and the patterns of how we engage with this notion of public space without codifying it, in a way kind of being part of it. And I love the questions that they present. How much of care is patience? How much of life is coping? How much of love is attention? They're reflective, they have this poetic sense of being part of the texture of the everyday.

Chloë Bass:

Thank you. That's wonderful.

Leonardo Bravo:

And they also don't clamor for or demand attention. Here’s the thing, pay attention to this thing, you know?

Chloë Bass:

I think in a lot of ways I am demanding it, but I'm demanding it very quietly because I think especially when you're working in a closer to monumental scale, a billboard is a closer to monumental scale with respect to human beings, you know, our relationship around monuments is that they're tremendously demanding both financially and in their shifting historic context and time. The production of a monument always sort of presumes that there will be a future where someone will need to understand that history in a certain way so that they have a sense of themselves in the present as also being a certain way. And those are oftentimes mechanisms of control. We think about that as now, I mean, like in a very contemporary way, we think about [monuments] maybe as an opportunity for representation that expands the mechanisms of control towards more people in different ways, but they’re still mechanisms of control. And I don't think anyone has found a good solution to that, even though there are some really lovely monuments that I can reference, right? But I'm sort of trying to offer an opportunity for what could a monument be that was not conceiving of itself in that way. Like what is the future that I'm presuming if I just want to put up a question, which I did in Los Angeles, that says, how much of hope is forgetting? Right? You know, like, who is that for? And who could they be by seeing that echoed back at a monumental scale.

Leonardo Bravo:

I think part of it is that space of the echo.

Chloë Bass:

That's what the reflection is.

Leonardo Bravo:

Yes! There's a reciprocity involved or suggested rather than a singular master narrative.

Chloë Bass:

The reflection is the visual echo, right? And the question can be the sonic echo, or it can be a call for an answer, right?

Leonardo Bravo:

Let's touch on a couple of other projects such as Obligation to Others Holds Me in My Place or The Book of Everyday Instruction.

Chloë Bass:

Sure. So my larger kind of schema, which I’ve talked about a lot of times, and it's kind of everywhere and people kind of know, but I'll say it again, is that I'm really just interested in intimacy. And the way that I'm going about understanding intimacy is by studying it at increasing group sizes. So I did a project that was really just about the intimacy between a person and themself called The Bureau of Self Recognition, which is not a recent project at this point at all. Then I did a series of sort of eight intersecting projects, which fell under the title The Book of Everyday Instruction. And all of those projects were about one-on-one intimacy. So partnership. And that could be between two people, but it could also be a more conceptual partnership, like the relationship between a person and their city, or the relationship between a person and the idea of safety. And then Obligation to Others Holds Me in My Place is the third major project cycle in this increasing scale model. It is about intimacy at the scale of the immediate family, and Wayfinding is actually one of the sub-projects of Obligation to Others Holds Me in My Place.

Leonardo Bravo:

I think this is always so fascinating, to have this through-line or this stitching of all the projects together. How did you get to identifying this sense of intimacy through these different scales of work and research?

Chloë Bass:

I think it's a genuine concern. I don't think it's an artistic concern. I think it's like a genuine personal concern.

Leonardo Bravo:

It's intriguing to me because I am so interested in this question of how do we take theory into Praxis. And to me, the only way theory becomes alive is through praxis, in the sense of engaging with the stuff of life in the everyday.

Chloë Bass:

I'm a person who's alive on this earth, and that means that I fundamentally have relations with other persons who are alive on this earth. And I think I've always wondered just personally, like, how does that happen? How does that work? Why do we do the things that we do? Why are we like this? So the intimacy concern is just, like, it's real. It's a genuine one. It's like a childhood concern. It just didn't go away. I can't make it go away. I don't understand it. Right. No matter what I do, I'm always like, but why?

I think optimistically as a person, I want to get from like, why to: how come <laugh>? So that's my genuine answer to the intimacy question. But the scale thing, it just seemed to me that we start from these very primary relationships, and yet society reflects back a lot of the same — both beauties and struggles — that are found at core of these primary relationships between us and ourselves, between us and a loved one, between us and our families. And so as I'm increasing the study by just expanding the group size, I'm just like, well, what is the same and what is different? What is the same across a few scales, then goes away and then reappears at the scale of the state? What is the same once and then surprisingly five times later, and then never again? I just need to do that work for a very long time and identify those things. But I'm an artist, I'm not a social scientist, so to a certain extent, my conclusions are rigged, right? Like this isn't exactly data-driven work, it's poetic work. What you do with poetics is very different. And how you prove something poetically is very different.

Leonardo Bravo:

I wanted to ask about inspirations, but also connected to your artist's statement where you reference various influences through categories such as rigor, connection, and creep factor; for use of language; for structure/archiving. Can you talk a little bit about those and the examples you used there?

Chloë Bass:

Sure. I mean, I'll pull it up so that I can reference it directly and not kind of obliquely. So hang on one second. I still stand by all of those things, <laughs>. So what I'm trying to do basically is demonstrate that I am an artist, but I'm an artist who is not just influenced by other artists, but I'm influenced by writers. I'm an individual, but I've been influenced by collectives. That I am someone who I guess now makes sculpture, but I come from a performance background so that I'm influenced by people who also work in performance. And that I'm into design. So I'm also influenced by architecture, right? And that's how we met originally, you and I, through architecture.

Leonardo Bravo:

We did. Yeah, a long time when I was doing my Big City Forum project, I think.

Chloë Bass:

And I was in grad school still.

Leonardo Bravo:

Oh, wow. Ok. So this is a nice circular way to connect!

Chloë Bass:

Great. And I don't really work in the architectural arena, but I've been enlisted through architecture as a person who's interested in design. Just this week actually I got an invitation to speak at an engineering school, and it's like a day that I'm super busy, I can't do it, but I was so excited. I wrote back, I have never heard from an engineering school before <laughs>. And the person very kindly was like, that's wild. I think of your work as being so close to data engineering in a lot of ways. And I was like, tell me more. So we're going to meet, actually, and I'm going to learn a little bit about data engineering from him, which is amazing. Beautiful, beautiful. Great <laughs>. Yeah, I'm very into it.

But, you know, coming back to this list of influences, right? So it's like Adrian Piper, brilliant conceptual artist, obviously performance-driven, language driven, deeply philosophically driven, and also has a very embodied practice through yoga and dance. Andrea Fraser, who I have had the privilege of knowing since I was about three years old. I didn't know who she was when I was three years old, but I have known her my entire life and although we're not in close contact right now, knowing her work, and sort of seeing how she dealt with institutional critique, but also other forms of self presentation, her pieces that have sort of reused or regenerated certain styles of language, I find that tremendously inspirational. Of course, she's also very brilliant as a theorist. I can't even aspire to be that brilliant as a theorist. But I do admire all of that. And her practice as an educator, I think is, you know, very strong and has left a really strong legacy.

Vito Acconci was my graduate advisor. So I was in a graduate program for performance and interactive media arts and Vito was my advisor, but also, of course, Vito is an architect and a poet. Yeah. <laugh>. So it's like performance, art, architecture, poetry, you know, there you go. <laugh> I'm not gonna smoke cigarettes and stay up all night. But other than that, <laugh>, there's a lot there and I miss him. Claudia Rankine, Frank O'Hara and Stanley Brouwn. Yeah. I think Claudia Rankine and Frank O'Hara are kind of obvious. I don't know that I need to say more. Like they're just brilliant in the ways that they write and for Claudia Rankine, especially her sense of connection that is clearly written between the institutional and the personal, right? And those frameworks of references. She's very strong in that. Frank O'Hara, of course, the great poet of the everyday.

But Stanley Brouwn is someone who I think everyone should be obsessed with, and most people don't even know who he is. He's a Dutch Surinamenese conceptual artist who made incredibly beautiful, especially smaller works that sort of directly or obliquely referenced the scales of being in everyday life. And several years ago I was asked by Hyperallergic to write about who I think the great overlooked artists of the world are and I wrote about him, and you know, he is in art history. He is in museums and galleries, but people truly don't know who this man was. And I think especially as someone coming through a slightly slant Dutch nationalist experience as a Surinamese person, I think I really see that sense of double vision and what it offers to the world in all of his work.

Also, his modes of presentation are just incredibly elegant. So, and then last like Group Material in terms of structure and archiving. Again I'm a very fortunate person, so I am connected with one of the former members of Group Material in my everyday life as a person who I know. And that has been a great blessing for me. But of course Group Material as such does not exist anymore, but also many of the people who were part of that are dead. Not many, but a bunch. Significant persons have passed. So not only does it not exist as a collective, but also it can't really be recreated in that way. It has become a historicized thing. But their modes of producing exhibitions and public artworks are completely everywhere and no one talks about it, so I just wanna talk about it. That's a great way to make political information available: to make exhibitions available as learning spaces to write, like even their use of just font and color and all of that stuff. It is so echoed out in the world absolutely everywhere. And most of the people I know who are doing it are not talking about Group Material. That's how well they did it. They got it into our aesthetic vocabulary.

And then the Eameses are, uh, I love a good chair, but also Powers of 10 as just the most simple scales document that there is — it’s a great way for me to say to somebody who doesn't understand what I do. I do this. Yes. But on the inside.

Leonardo Bravo:

You mentioned you started out training in primarily performance and you also have Vito Acconci on that list.

Chloë Bass:

I started in theater, straight up theater, in undergrad. And then I went to a performance and media grad program in part because the economy was in the toilet and I didn't really wanna go to grad school, but I live in New York, where the City University of New York has a wide range of fairly affordable graduate programs. And somebody told me about the Performance and Interactive Media Arts program at Brooklyn College. And what interested me about it was actually that it's a fully collaborative program. No one makes work on their own. And I was like, that sounds weird, I'll do that.

Being there was tremendously informative though, because the program is a collaboration between many different departments at Brooklyn College, so fine arts, theater, television and radio, computer science and music, are all collaborating to bring this program together. So it's extremely interdisciplinary. And so for me, coming from a theater background, some elements of my prior education were referenced, but I was also just exposed to a whole bunch of other things that I'd never heard of before. Things like social practice. Things like programming with Max MSP, and interactive technology. I'm not gonna say I found everything that I was exposed to equally resonant for me, but it didn't matter because it just gave me a sense of what the wider world of practice could be beyond making a play, which was all that I knew how to do at the time, and something that I wasn't necessarily interested in always doing in such a formalized way.

So the program offered me the potential to understand that performance was something that was existing in the art world. And at that time, 2009 to 2011 was, like, Performa is happening, it was a big moment for performance, very popular. And so [I had] the ability to see a lot of how performance was differently operational in the art world than the theater world, or in the music world than the art world. But also that there's space for other modes of creation that qualify as live art that could happen in a gallery or a museum, which I had kind of been exposed to as an audience member, but never considered as a maker. And so that was slowly the beginning of me moving from theater world to fine art world, which was a very gradual transition.

And that's when I met all the architects too. And then later the poets came for me and they were like, you're a poet. And I was like, I just like words. And they were like, you're a poet, let's publish a poetry book. And I was like, well, I've never written a poetry book. And they're like, this thing that you wrote, we'll publish it as poetry book. Which is tremendous when other people are open to your work in that way.

Leonardo Bravo:

It's amazing as we're talking is that you have such a broad palette or toolkit available at your disposal, to really get to this notion of what is it to be human and the psychological and emotional sense of how we engage with space, with public space. So related to that, how do you center your work around social and cultural histories and how is that reflected in your practice, especially as the work exists in public space, in the realm of the everyday?

Chloë Bass:

You know, taking on the project of social and cultural history is too massive for anybody. But I also am aware as a person that there's all these things that come from the past that deeply interpret our present, even if we think of those interpretations as isolated and contemporary. I'm also aware as a person who really struggled with the study of “social studies” in high school, which is American for History, it was not an easy subject for me to master, and my dad had to help me a lot with it. And one of the reasons it was not an easy subject for me to master is because it was so much about things proceeding in a linear fashion. You just had to know when something happened, and then the next thing happens, and the next thing. And I was just like, I can't make this make sense in my brain. And my dad was like, you just have to memorize it. He — I’m not saying that's correct educationally, but — if you want to succeed in this topic, you have to memorize it and I'm just gonna help you memorize it. And I was resistant to it. I was able to do it. I've generally been a pretty good student, but, like, that being at odds with my interpretation or understanding of how the world was, is something that also started pretty young. And my sense that whenever anything is happening, any single event, lots and lots of other stuff is also simultaneously happening, whether incidentally or on purpose. And that there is no field that really accounts for that yet. That is how we live. And what makes it into history is only these sort of very exceptional acts, or days or things that fit into the story very smoothly, and everything else is kind of tossed out.

Leonardo Bravo:

And I would say it's also a particularly sort of American exceptionalism in terms of history and this kind of linearity that our American narrative is the only one that's occurred.

Chloë Bass:

For sure. For sure. And like, not just our American narrative. Like our North American, United States American narrative. My mom is from the Caribbean, she's from Trinidad, and that's the Americas as well!

Leonardo Bravo:

The same in Chile where I'm from. South America is the Americas.

Chloë Bass:

And within that there's tons of different cultural specificities, histories, stories, languages, whatever. But, like, this idea that history is written by the victor, I think could be seen not just as a personal thing, but as a sort of exceptionality of event, or content, or even individual. So I don't think I can take on all of any particular social or cultural history, but I'm trying to take on this idea that, like, what is there has been constructed. And in art you're able to do quite a lot of construction, both physically and conceptually. And because I also work with language, I can do it narratively, and kind of unraveling that you can make anything seem obvious whether or not it happened that way, or is true. But as an artist, I have the freedom and flexibility to connect any two things and suddenly they take on a different meaning. And in art we call that maybe, like, a revelation, <laugh>, but in history we call it a lie, or irrelevant. So, you know, why don't I just use art to demonstrate what history has made false or oversimplified.

Leonardo Bravo:

Finally, what is inspiring you right now? What are you admiring and kind of touching you?

Chloë Bass:

I mean, so because I've been working with glass for the first time, my glass fabricator is actually out in Pasadena, at Judson Studios. And I'm really inspired, the guy that I work with specifically is Quentin and he's my age, but has been doing this for like 20 years already, which, you know, I was in high school 20 years ago! And I really have been so inspired by his knowledge, and his process, and his grace in this very delicate and weird material that is like a super cool liquid. So I would say like materially that has been one major inspiration.

I think personally , in a genuine but kind of cheesy way, my students this year have been really exceptional as a group. And I'm always telling them, I'm not making any statements about individual genius, but I would say, the 13 of you together are a genius. Like, you're operating on like a group genius logic, even though they're not, we're not a fully collaborative program, right? They're together a lot, but they're not necessarily making work together. But I'm like, there's some collective genius group logic that has really been consistent. And I work with them all year, so it's not like I’ve just been working with them for seven weeks, right? We're in the last seven weeks of a 30 week cycle together and so far we've had no bad days. I'm quite inspired by them!

Leonardo Bravo:

And to feel that collective group energy being harnessed and not just by you as the expert, but as the group itself.

Chloë Bass:

Definitely! And I think also coming out of the pandemic, and last year at school, we only had half a year in person. We didn't go back until the spring semester of last year. So people were in a pretty bad space. It was awful. Honestly, last year was awful. Just emotionally, people were in bad shape. And so this year my expectations were, like, moderate at best. And so that it's been a really exceptional and connective year I think is extra delightful.

Leonardo Bravo:

That's beautiful. Chloë, thank you so much. This is wonderful to reconnect and as you're right, we did meet in person quite a few years ago. And again, so impressed and touched by your multivalent practice, the way you bring these different components together, ultimately in very poetic ways.

Chloë Bass:

Okay. It was nice to talk to you.

For more info: https://www.chloebass.com/

IG: @publicinvestigator