Kaleidoscopic No. 14: John Brooks, Pt. 1

moving through the world attuned to emotions and moods..

Leonardo Bravo:

Welcome, and good morning. I'm doing an interview with John Brooks an artist based out of Louisville, Kentucky and whose work I've been following for the last year and has touched me in many ways. This is a great opportunity to learn more about your practice, your inspirations, and your own journey as an artist and a poet!

John Brooks:

Thank you. Very happy to be here.

Leonardo Bravo:

I thought we'd start by what drew you to be an artist, some of your inspirations, and the touch points along your journey.

John Brooks:

My journey to become an artist was a long and circuitous one. I grew up in central Kentucky in the eighties and early nineties. I was always interested in art as a child and was sort of put in that category. I was thought of as an artist at, at school and amongst my fellow students and family. But there was not really a tradition of truly engaging with the arts in my family. In my mom's extended family there was a tradition of music and perhaps some writing, as her father worked as a kind of journalist, but no visual artists. And then on my father's side, his father primarily worked as a foreman in the boiler room at the Old Grand-Dad distillery.

John Brooks:

So he was a blue collar laborer but he was a very good artist, actually, and he could draw very well. And in the 1950s and 1960s, he had a sign painting business with a friend, they would paint delivery trucks and billboards and that kind of thing. And in fact, his mother, in the twenties and thirties, was, in our kind of relatively small town, the woman who arranged the window displays in shops. So, yes, there was an artistic touch but it was more oriented toward practicality more than expression. Part of that, of course, has to do with economics, my dad's side of the family were definitely working class.

Although there was some peripheral knowledge of art, it really was remote. I was enamored with all things art as a kid, and I drew all the time. I was given materials, but it never occurred to me that this was something that I could pursue as a career or as a life path.

John Brooks:

Also, my father was a parks and recreation director for almost 40 years. My mother was a teacher. I was encouraged to play a lot of sports, never forced but encouraged and luckily for me I found golf at a fairly early age and as a gay kid growing up in the eighties in Kentucky playing team sports, it was not an environment that I found comfortable. When I came to golf it was something that I could do outside, which I liked, and then it was largely individual and I got to play with adults, and so it's important because that became kind of my identity. I became very good and I played a lot in high school and college and played competitive golf for a while after college.

So golf kind of became my focus, but I also had a desire to study art in college. Most of my friends were art majors, and I did take a handful of art history and studio courses, but it was still not something that I felt was a possibility for me at all. There were limitations that I felt had been placed on me by the realities of my upbringing but also there were limitations that I’d put on myself.

John Brooks:

I wanted to be a professional golfer which, at this point in my life, seems like a whole other identity, really almost someone else’s life. But that was my focus for a long time. I was also interested in political science and literature and writing, so I majored in those things, thinking that if the golf didn't work, I'd do something else like pursuing law or writing. A few years after I graduated college, I met my partner and then a couple of years later, in 2005, we moved to London because of his career. I was at the end of my journey with golf, a path that I had pursued since my youth.

John Brooks:

I arrived in London with absolutely no idea how my life would be or what I would do. But I very quickly decided to simply do what I wanted, which was to explore all of the art that London had to offer. And there's so much that's there, there are so many incredible museums and galleries and collections. It feels endless, and moves backward through time, through the spectrum of art history, as far as possible. I just started seeing all I could and then, being inspired by everything I was seeing, started making some work again. Prior to that, I had made work here and there, but really did not have a body of work to speak of.

I also started taking some studio courses at Central St. Martin's as a continuing education student, not enrolled officially in the program. And I very cautiously started referring to myself as an artist when people would ask what I did or who I was. There's no doubt in my mind that had I not moved to London, I wouldn’t be working as an artist. This interview would not be happening. After the kind of life and career I had envisioned for myself had not come to fruition, I was forced to start over, to reimagine who and what I could be. In London, I was in a place where no one knew me, so there was a lot of alone time, a lot of time for introspection, and I was really able to explore parts of my person that I’d never explored before.

John Brooks:

I was so lucky to be in a place like London, which is so incredibly rich with history, art, and culture, and where no one batted an eye when I said, I'm an artist. Because, well, they exist <laughs>. Whereas, growing up, I didn't know anyone who was an artist, it just as if they didn't exist, or if they did, it was in the part or in cities I’d never get to. So it was a very long path to get to that point and again, I was 26, 27 and then now I'm 45. So the the second part of that path has also been long and it's really only been within the last maybe three years that I feel like things are finally coming together.

Leonardo Bravo:

Quite the journey! Especially what you said about your dedication to golf which probably required a great deal of rigor and discipline as well as focus. And you probably took those very same qualities into how you eventually immersed in being and defining yourself as an artist.

John Brooks:

I suppose I did. They seem incongruent, but if you look at them abstractly, they're really not. Golf, like any skill, requires a lot of rigor, practice, dedication, and it was very much my life for many years starting around when I was 12 years old. I started my first summer job at that age. At six o’clock in the morning, I would walk to the municipal golf course where I played, I would clean the bathrooms, clean the golf carts, and then play golf all day. All summer. That was my life for years, so I am accustomed to working really hard.

John Brooks:

The other thing I think that's interesting that I only recently realized is that while I was a very good player—I had an excellent short game, like around the green, putting, and things like that—but my overall game was a little scrappy and I had to be creative in order to compete. I had to learn all of that creativity myself by doing it, as opposed to studying technique. Obviously I had some technical skills, but technical skills are only part of what makes someone good at something. Actually making something happen takes more than knowledge, it takes a kind of creative impulse and creative will. And so there is a correlation there with my artwork because, while I have had some instruction, I am largely self-taught and almost everything I've figured out how to do, I've figured out by looking really hard, paying attention and doing.

Leonardo Bravo:

That's fascinating. Much of what I take from your work is this attunement to a sense of memory, longing, and desire. But there's also a clear commitment to deep observation that you bring forth and paying attention to moments and stories. How do you see that reflected in the work and in the context of your own history as well?

John Brooks:

I am someone who has always been very observant. I look at things, consider things, I pay attention and I sort of move through the world attuned to emotions and moods. Some of those things just exist in the natural world, like the mood of a day or something like that, but they’re only palpable if you’re paying attention. I'm a curious person and I've always been interested in almost every subject, with maybe the exception of math <laughs>.

John Brooks:

But literature and geography and history and cinema, and everything! When I first started working as an artist, I did consider going back to get an MFA or even an art degree, like an undergraduate degree. I didn't do it because we kind of moved around for a few years and the timing just wasn't right. But in the beginning, there were many years where I felt I was at a disadvantage and almost embarrassed not to have this degree, and that I did have this political science degree instead.

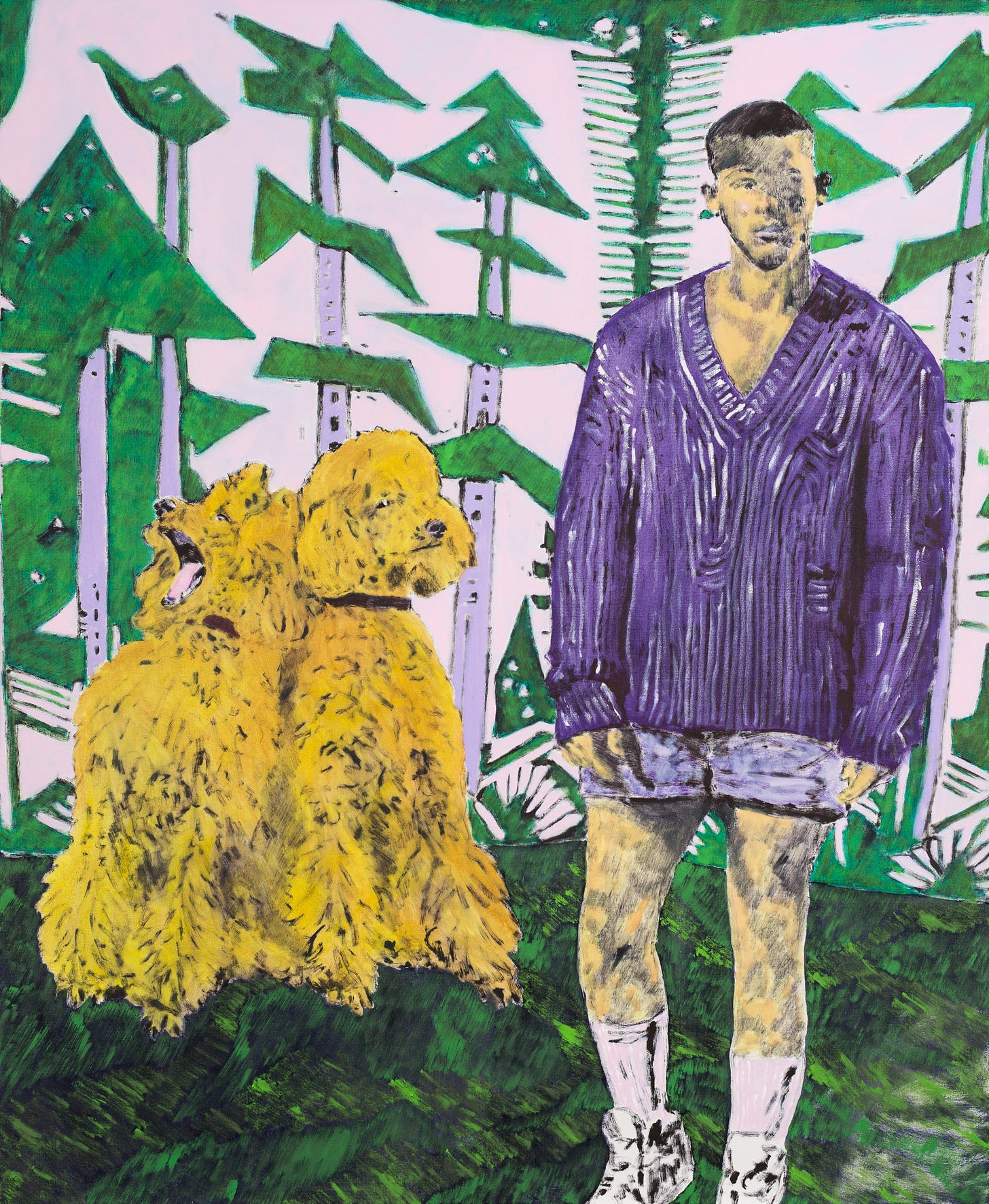

I don't feel that way anymore. A few years ago I finally understood that everyone has different skills, different abilities, different things that they bring to their practice. One of the things that I bring to my practice is this kind of intellectual curiosity that spreads out across all kinds of subjects and I’m able to use all of that to infuse it into the work. For example, in the show that I had in 2021, “We All Come and Go Unknown,” there was a particular painting that was a catalyst for so much of what I've been doing since. In this painting, I combined an image of Nick Jonas with these two oversized golden standard poodles.

John Brooks:

And then the background is borrowed from a Karl Schmidt-Rotluff woodcut. And even though it's similar to some work I had been making, there was something about combining these three things that felt lie a step in a different direction. Initially I thought, no, you can't do that. That's too weird. These things are too disparate. But the more I thought about it, I realized it was exactly what I needed to do, that probably only I would put these three things together, as the number of people who are influenced or are even interested in these three things is probably pretty small.

But there was strength in that. There was value in that because it was creating something new by combining these peculiar elements that have different cultural, historical weight and contemporary resonance.

Leonardo Bravo:

I wanted to talk a little bit more specifically about some of the pieces, and I'm looking at a work like Mind Over Matter as Magic. What impresses about the work is the way you use line and color and the quality of the touch of the hand, but also what you're positioning creates a space for liberation. I feel that these works are ultimately about liberation; a liberation of queer identity, a liberation of being in the world. The lush intensity of that experience. There's such an expansive quality to what you're trying to convey, especially as you're talking about these counterpoints or the tension between elements that might normally go together, but how those juxtapositions create frictions, create expansiveness, create space that allow for new possibilities and meanings to emerge. And the new possibilities are liberatory.

John Brooks:

Exactly. I think when an artist creates work with unexpected juxtapositions, it is precisely that tension that makes something interesting. An artwork isn't a math problem. As I see it, it is something to be experienced and it is the sense of unknowability that compels you keep looking at it. If you look at something and understand it right away, I think you stop looking at it. Obviously there are also aesthetic pleasures. But if you're looking at something and it catches your interest because of these sort of peculiar juxtapositions, exactly as you say, it creates an expansive, almost infinite amount of possibility. And so that's kind of how I've come to see the work. It's a space where those things are possible.

Leonardo Bravo:

And the works brim with energy and emotion. There's such a tactile quality of the line, the colors, the way you work the surfaces. Can you speak about those formal choices and approaches and then some of the influences? I mentioned to you that I see much of early Hockney, and Peter Doig, Wayne Thiebaud, but even going back to mannerism in the Renaissance, someone like Pontormo, who was working with these vibrant and rich hues; pinks and oranges and saturated greens. Even your historical references, for example there’s so many references to the Weimar Republic in Germany, and that period of unfettered freedom and expansiveness in German history as well.

John Brooks:

I'll start with that since that's the last thing you mentioned. It plays an enormous role in my work and in my life. I mentioned my grandfather earlier who was the foreman in the boiler room. I have his signature tattooed on my chest. We were very close and spent a lot of time together. He was an American soldier in World War II, he fought in five major campaigns in Europe including the Battle of the Bulge, the Hürtgen Forest, so he was in France, Luxembourg, Belgium, and Germany. He also had a photographic memory, so growing up I heard a lot of stories about and exposure to that time period through my own family lore.

John Brooks:

I was naturally intellectually curious about that time period, and as I grew older, there was a convergence of my interests in history, literature, and art, and also as a Queer person. So much emanated—for better and for much, much worse—from Berlin. Berlin and wider Weimar Germany played a central role in the lives of so many of the artists and writers that I care about. And in the last few years, unfortunately, fascism is on the rise again around the world, and this history is very relevant; the experiences of World War I, the Weimar Republic, World War II and the lessons I think collectively we had assumed that we had learned. It’s clear that either we didn't learn them or we've forgotten them. Some elements of this history are not fully mine to tell but I am doing what I can to bring forth things that I think are important, things that I think deserve attention, into the present, hopefully pushing them into the future. I'm connecting to them in a variety of ways as an artist and as a Queer person. Take Marlene Dietrich for example, who figures in a number of works. We’re having all these discussions and arguments about gender expression and such.

John Brooks:

Dietrich was dressing in tuxedos and mens clothing a hundred years ago—and causing kerfuffles. We've already been through this, and not that that knowledge can end that discussion or solve this disagreement, but maybe people don't know this history. Helping to shine a light on that is something I'm interested in doing, but also I connect with her just as a human being and as an artist. You asked about some formal decisions. The work changed quite a bit, really entirely changed in 2018 when I made a decision to start using my collage practice as a basis for composition for my painting practice.

John Brooks:

For years, I had both a painting practice and a collage practice. They were not integrated. The painting was still figurative, largely kind of oriented around the face, but it was looser. But I had reached a point where it wasn't working for me. I had no idea what to do. I actually decided to give up painting and then somehow I kind of worked through that and realized, no, I don't want to do because, I like working with paint. I like working with oil paint. I like the material.

John Brooks:

And I came to see that for me, my problem originated with composition, and that I just didn't know how to start. I was working with this idea that like, oh I can do anything, and that sounds great and maybe it works for some people, but for me it wasn't working. And I realized that if I started using my collage, like literally my physical paper collages as a basis for these first paintings, that gave me a framework and within that framework, there was so much more freedom to work with the material. I'm no longer making physical collages but the mindset is still there.

Leonardo Bravo:

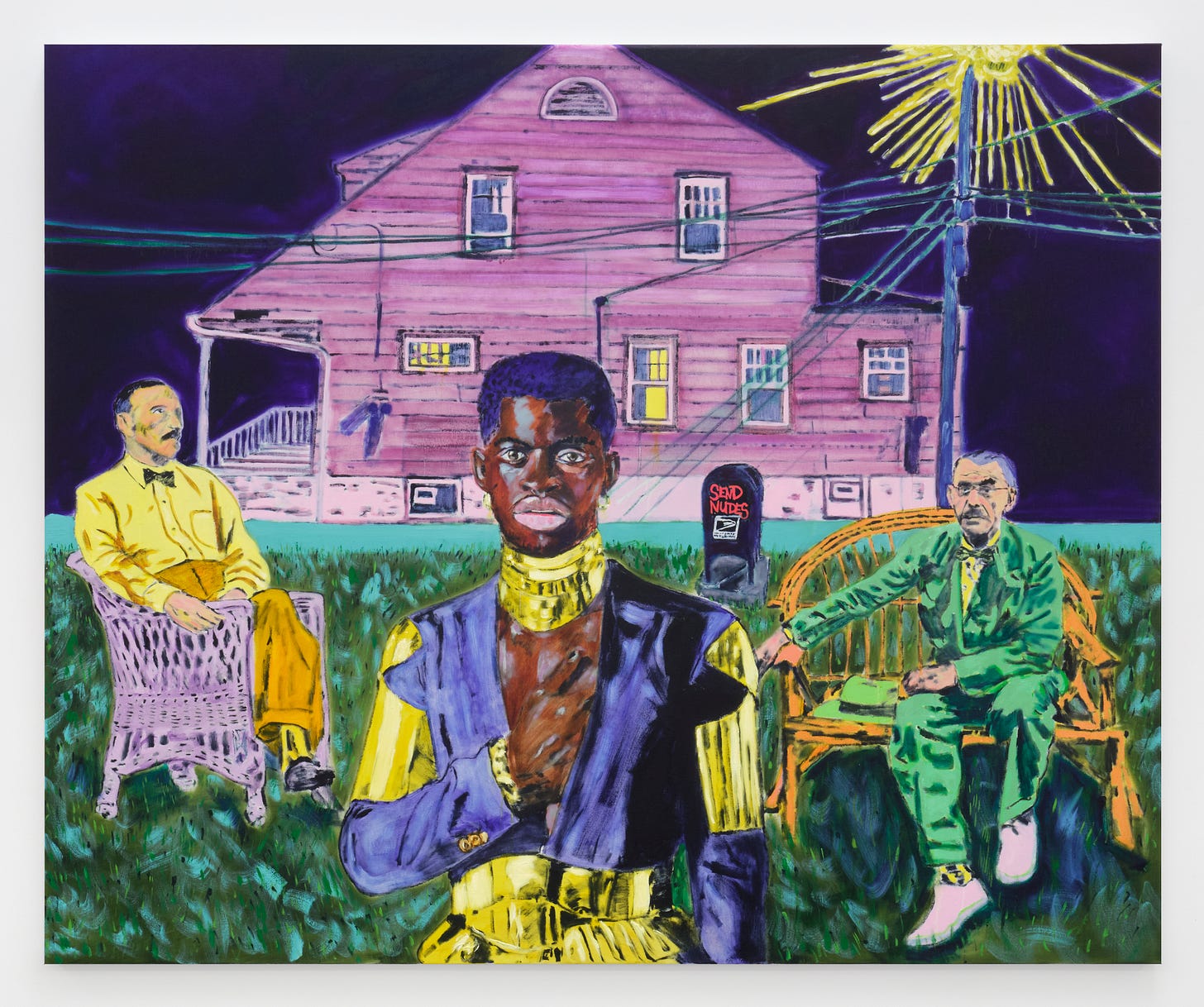

Can you talk about the show at Luis De Jesus Gallery in LA, your Thinking About Danger exhibit and a work such as Hello Friend from The Road, which I believe includes Thomas Mann, and maybe, is that Herman Hesse?

John Brooks:

It's Stefan Zweig!

Leonardo Bravo:

Oh yes.

John Brooks:

And the other one is Lil Nas X

Leonardo Bravo:

Wow. Yes!!

John Brooks:

That was the last painting I made for the show and to that point, it was the largest painting I'd made, I mean, it's pretty big about 66 by 80 inches. And the space at Luis de Jesus is so incredible. I felt that I really needed like, something bigger within the context of that gallery space. And believe it or not, before the exhibition, I'd actually never been to LA, even though I've traveled a lot. Somehow I’d never been there, but I've always been interested in the city for any number of reasons.

John Brooks:

Cinema is a huge interest of mine, but also literature. Christopher Isherwood was there, well so many, Isherwood and Thomas Mann, so many European exiles were drawn to LA, so I made that painting partly with that in mind. I collect images, and I'd had this image of Mann that I'd been wanting to use in something, and I felt like this was the perfect time because the painting would be in LA. When I'm making one of these clearly collage-inspired paintings I like to start with an image or a person in mind. And then I go through my cache of images and think about what could go with that, what could be created by combining. Sometimes I have like two things in mind that immediately just go together and sometimes I don’t, the concept has to develop over time. I was thinking about Thomas Mann and then I was thinking about Stefan Zweig who is another of my favorite authors. He left Europe because of the rise of the Nazis and settled in South America and later committed suicide in Brazil. He and Thomas Mann were acquainted, and of course, I’ve seen them described as “neither friend nor foe.” Mann came to LA with so many other German and largely Jewish emigres and exiles from the war.

John Brooks:

I was thinking about more contemporary culture and something made me want to put Lil Nas X very much at the center of that painting. All of my titles generally come from literature or song lyrics or cinema, it's always some some kind of point of reference. But I wanted the title of that painting to be taken from Lil Nas X and his song Void, even though we have these two giants of literature from whom I could have chosen scores of titles. There are some connections bizarrely between these three even just very loosely, there's some queer references with Mann and things like this. So I was just imagining like what kind of conversation these three would have.

Leonardo Bravo:

Did you know that Thomas Mann's mother was born in Brazil?

John Brooks:

I didn't know.

Leonardo Bravo:

Yeah and there's research work that's been done in Germany about how this part of his story radically alters our reading of him, especially as he came to define so much of what might be considered "Germanness" during the 20th century.

John Brooks:

That's so interesting.

Leonardo Bravo:

There's also this whole element of Mann having a more complex and felt understanding of the global South from a colonial perspective and also the struggles that his mother encountered as an immigrant to Germany.

John Brooks:

Oh, that's incredible. No, I didn't know that. What was amazing to me, when I had my show, a friend of mine from my town, who's about 75, said I'm going to put you in touch with a friend of mine who has lived in LA for 30 something years and make sure she comes to the opening. She came to the opening and I was showing her around, and showed her this painting.

John Brooks:

She is friends with Randy Schoenberg, who is an attorney and the grandson of Arnold Schoenberg.

John Brooks:

The Austrian composer who was targeted by the Nazis, came to LA and was in Mann's circle of European emigres in LA. And Randy Schoenberg was the attorney for Maria Altman in the Adele Block Bauer case, the Gustav Klimt, the Woman in Gold...that whole story. And so, although this woman didn't know Thomas Mann, there was like one degree of separation, of this lineage.

John Brooks:

It also shows the power and really the motivation for including these historical figures and historical references; they are very much relevant. Because these lineages don't disappear, they continue. One of the really interesting takeaways from the solo show I had in Louisville in 2021, which was called, We All Come and Go Unknown, which was the show that Garth Greenwell wrote about in The New Yorker, was that so much of the feedback about the work was about color. I am interested in color, I've always been interested in color and every color in every painting has been chosen purposefully. But I wasn't even really consciously aware I was doing that. My concerns about color were secondary or tertiary, it wasn't something that was at the forefront of my mind.

Leonardo Bravo:

Interesting. It’s so present in your work with the ability you have to use color and infuse it in the work.

John Brooks:

It has now become something I'm actively pursuing. I was already doing it because I made those paintings, but previously it was more instinct than something that was really pondered over. Again, that is one of the reasons that in my own mind I had to fight for continuing to be a painter because I love working with oil paint, because of its quality and because it is so luscious. So it is just peculiar that I was more concerned with content, you know, with the figures and with the meaning. This is why you show your work to other people.

…interview to be continued in part 2

https://www.johnedwardbrooks.com/

IG: @narcissusandgoldmund