Leonardo Bravo:

Hello this is Leonardo with Kaleidoscopic Projects, and I’m here with Edgar Ramirez. An artist based in Los Angeles, whose work I have been following and been intrigued by the scope of his practice, both conceptually and formally. I’m happy to do this here directly from Los Angeles as I’m back from Berlin for a little bit and getting to have this conversation early in the morning with Edgar. It’s wonderful to connect and be able to have this conversation with you.

Edgar Ramirez:

Hi Leonardo. Thanks for having me! I really appreciate your connection with my work and being interested in wanting to talk more about it.

Leonardo Bravo:

Absolutely. I wanted to start off with a general sense of what drew you to be an artist, some of your inspirations along the way, either through your upbringing, family, education, sort of what brought you up in the arts?

Edgar Ramirez:

Growing up I wasn’t exposed to the arts, but during high school I was referred to this program. It was called the Ryman Arts Program, and at the time it was on the USC campus. So, the idea of pursuing art was incepted there, plus I had an outlet to draw. But it was something that I wouldn’t come back to until maybe 10 or 11 years later.

Edgar Ramirez:

The teacher that I had at that program was from Otis College of Art and Design here in LA. So, Otis just stuck with me in my mind. And because of that, I applied and got in, luckily for me. I didn’t think I was gonna get in, but once I got to Otis, it was just like a different world. I didn’t think I was gonna go in there to get what I did coming out of it. I thought I was gonna go there to draw and I quickly realized that I did not like to draw.

It was because my perception of it was like being a hyper realistic artist, drawing people, and just getting the figure right. And it was kind of this thing that I wasn’t interested in anymore. So, I think the first two artists that I was really introduced to were Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelly.

Leonardo Bravo:

Oh, there you go. That blew your mind!

Edgar Ramirez:

Yeah! It just I didn’t know what I was looking at. But it was really interesting that all these people around me were interested in these works, and it was just exploratory from there on out. And by the end of my time at Otis, I realized I needed to continue to pursue this way of thinking. I was fortunate enough to get into a graduate program that really expanded my mind to these ideas and interests that I have.

Edgar Ramirez:

I got into ArtCenter in Pasadena. So, to me it felt like an extension of what I was already learning. And it was really nice because a lot of the community at Otis was friends with the community at Art Center, and it seemed to have connections to Cal Arts. Because of that I felt like it was the right moment for me to jump on board. Now I feel like I’ve gained a better understanding of myself and my ideas and what I’m really interested in talking through with my work.

Leonardo Bravo:

Yeah. Absolutely. It’s quite a journey. It’s interesting because myself as a young undocumented immigrant to the US, I felt very much in the shadows, in the margins, but luckily through my interest in the arts and my own commitment to it in high school I was encouraged also to find Otis. And I went there in between junior and senior year of high school, and I thought, wow, this is like a whole world that I never even imagined, you know?

Edgar Ramirez:

Yeah. Exactly. I mean, growing up, and I feel like it’s like this for many minorities, we’re not really aware that these things are out there for us. I think the most important thing for me was this way of thinking and really asking questions. When I was younger, being around the people that I was with, and not necessarily in school, but it felt like asking questions was a bad thing. There was this sense that asking questions was dumb. Yeah. And it wasn’t until I was at Otis that I was encouraged to ask critical questions like there’s no dumb question. I think it’s important to encourage asking questions and asking why things are the way they are.

Leonardo Bravo:

That’s central because I think in a sense that’s what your work does, is to question the the structural and systemic issues of built into capitalism. And the issue is that you are not encouraged to be a critical thinker. Capitalism doesn’t want you asking those critical questions. It wants you to be a sort of passive observer, passive consumer of the experience.

Edgar Ramirez:

Yeah. Absolutely. That totally ties into the work and where I’m from. I grew up in the port of Los Angeles, which is maybe half an hour south of downtown Los Angeles, and it’s very industrial.

Leonardo Bravo:

So, it’s half an hour south, but it’s also almost like worlds away.

Edgar Ramirez:

It does feel like it. Usually when I describe where I'm from I have to describe the surrounding communities like Long Beach and San Pedro. I'll tell people I'm from Long Beach because they have no idea where Wilmington is. It is a different world because it's so industrial and we're surrounded by oil refineries. Any way you enter that neighborhood, any direction, there's a refinery. And then of course we have the largest port in the US when combined with Long Beach Port. So I think about this economic connection to the city and the economic disparities you notice once you enter the city.

Leonardo Bravo:

This is a good segue way to get into your work. Can you give a sense of where your work is at and how these ideas have been developing for the last few years in the scope of the work.

Edgar Ramirez:

I've always been interested in this idea of neglect or deterioration as far as a surface is concerned. And I started looking at these things primarily because of where I grew up and where my mom used to work. My mom was a housekeeper, and she was working in these nice neighborhoods. There's this hill that's overlooking our city and it's an upper-class neighborhood, and from an early age I never understood why it was so different from where we lived. And it was just something that stuck with me.

Edgar Ramirez:

While I was in school, I started asking these questions of why certain things exist in our neighborhood, particularly like these predatory loan posters that are marketed to people that are wanting to buy houses. I started noticing little things like that. I do wanna say that it was through the lens of Mark Bradford because if I hadn't seen his work, I probably wouldn't have gotten to the point I'm at now. But I started noticing what he calls these merchant posters, and my interest was more in narrowing it down to a certain type of poster. And it was really these loans and credit reduction scams. It all comes back to the financial aspect of it. And I started noticing a lot of these signs pointed to the same phone number.

Edgar Ramirez:

I started wondering why one sign would say real estate loan, the other sign would say Government home loans, another sign would just say Fast Cash. But they would all have the same phone number. And through that I started noticing these signs in certain types of neighborhoods and the kind of jobs that were being produced by this industry.

Edgar Ramirez:

I have a background in production line work and being in production we're just always expected to hit a certain number at a certain time. So, it becomes this sort of wanting to work in a machine-like pattern. So, I started putting all these ideas together, just digging into it and seeing what I'm noticing as common threads throughout these communities. And not just mine, but communities throughout LA and places that I've been to, particularly in Mexico and India.

Edgar Ramirez:

I started noticing the differences in classes in these spaces. And I think that now I look at everything from a socioeconomic standpoint.

It's very important to me, and everything that comes out of that and how I relate to it and how the surrounding communities look, and they tend to look a little more beat up and gritty – That is what I put in my work.

Leonardo Bravo:

That's profound. This whole sense of the predatory system that preys upon the false hopes of working-class, low-income folks. At that local community micro level it's so present, but when you pull out to every community in America, there's the predatory sense that capitalism is constantly preying upon you in larger or small ways. It is structural. And I mention that because after spending time in Berlin for a while now, you don't feel that, you don't feel that that psychic pressure that is here in America, to be part of this system that's constantly pushing you to consume, to be in debt, to be indebted to something, to have more, and consume more. In Europe, sure it's a free market system as well, but there's a different register and different relationship within the social context and the social setting of things. You don't feel this constant pressure to consume and participate in that way. And like you mentioned, you see these economic extremes here in America. They're endemic. These extreme relations to affluence, and then all of a sudden just down there, it's extreme inequalities.

Edgar Ramirez:

Yeah. And it's so fast. I mean in LA you have to drive, and I'm so used to driving from a young age, but if I take any of those big streets facing north, it’s gonna happen immediately. That change. I mean, for instance in low income areas you're gonna see concrete, not much greenery, food deserts, and run down spaces. Then immediately you just see that change to lush, green, and abundant. It's pretty amazing to see that change but it's also kind of sad to see from my perspective, the money distribution. You can see the separation and the gaps.

Leonardo Bravo:

So how do the socioeconomic issues and factors that drive the work, how does this inform the formal aesthetics, the material qualities of the work, which I find so powerful and intriguing?

Edgar Ramirez:

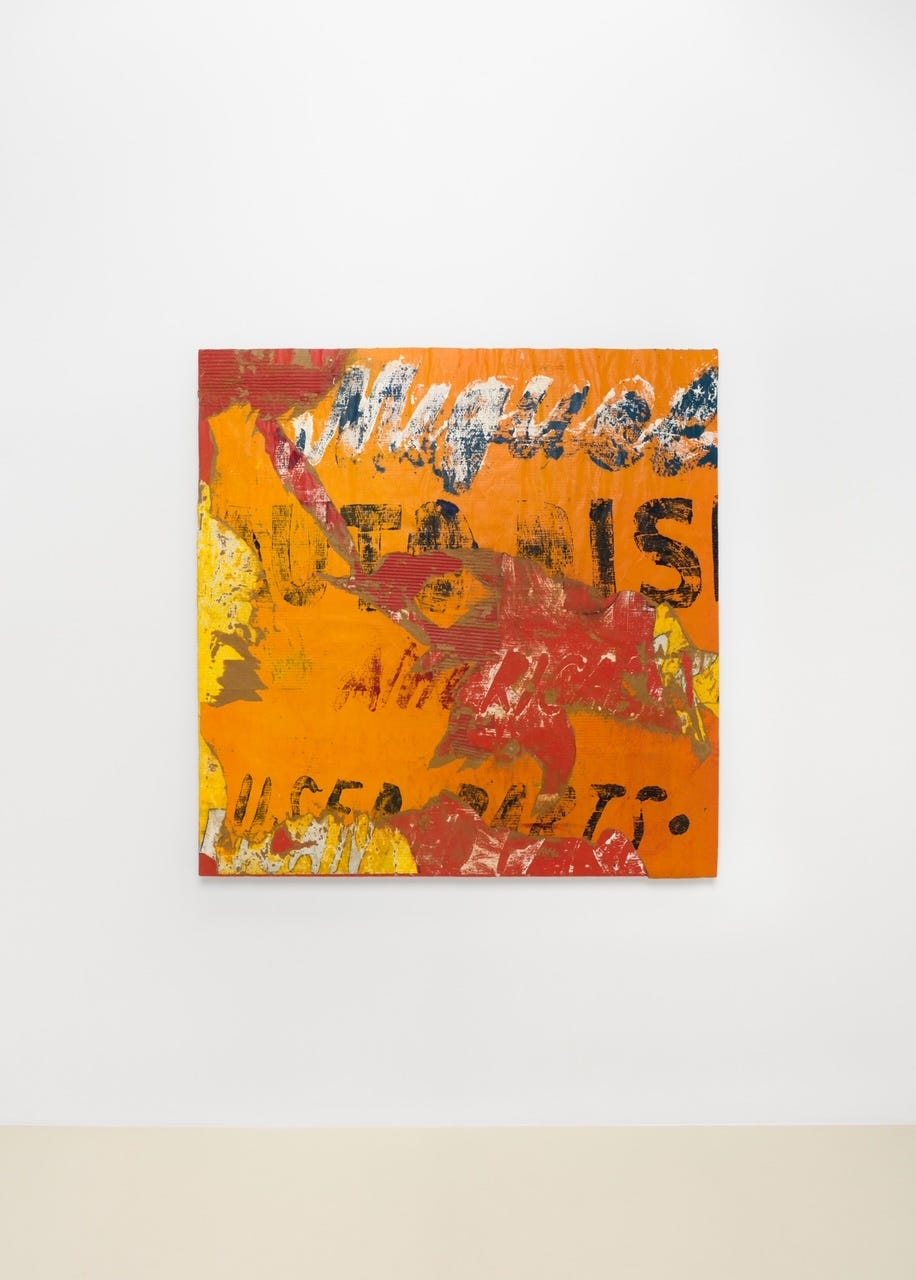

I'm really interested in these surfaces of deterioration and neglect. What I think about are these warehouses or shops that surround the industries in the neighborhood of Wilmington. I find myself interested in those that are pertaining to intensive labor. The more I think about it, these exteriors are either neglected, abandoned, or there's just no time to really make them look good because of the jobs there. Plus, this sort of weathered aspect to the exteriors, especially when it comes to shipping containers, they're always present and they're always changing, and the way these containers get beat up and the layers that are revealed through erosion or just the wear and tear. I think of them as fragments and of taking pieces of them and bringing them into my studio, that's the way I think about these works.

Edgar Ramirez:

But I use cardboard and it's this material that's very ubiquitous and it's also a container in itself. So, it's similar to the shipping containers. There's like boxes and boxes of cardboard. And I find it interesting that there are also layers that make up these things. I'm very interested in the makeup between these layers, which is why I do it this way. And it also relates to the stacking of the shipping containers and the lines of the shipping containers because I still think of my work very much in terms of drawing.

Leonardo Bravo:

That's interesting. I can see that.

Edgar Ramirez:

So, the process is that I'll take sheets of cardboard, it's normally like new cardboard that I receive, and I'll strip it down and I'll paint layers on them, and I'll add some texts through stencils. I make my own stencils and I sort of take this print like approach. I'm not a print maker, but I used to make credit cards, so a part of making these credit cards was that you had to print and emboss. So I'll layer up the cardboard and then I'll strip it down, rip it up, and sometimes it is this sort of violent action.

Edgar Ramirez:

And at other times it's very kind of like…

Leonardo Bravo:

Seductive

Edgar Ramirez:

<laughs> In a way yes! It's not always just using my body, which I do, but sometimes I gotta get in there and really kind of rip, I gotta direct the rip. But it happens very organically too.

Leonardo Bravo:

It's interesting you brought up Mark Bradford but then I also I see so much of the European post-war artists like Mimmo Rotella or Alberto Burri who were looking at materiality, from the perspective and being informed by a post-war kind of decay, the way so many cities had been destroyed and much of Europe was in a psychological and physical rubble. I definitely saw Mark Bradford, but I think you have a quality of approach to the way you're pulling these materials that also makes me think of the sediments, you know the geological sediments of history...that push and pull.

Edgar Ramirez:

Yeah. I think very much so and that group, the Affichistes, artists like Jacques Villegle, Raymond Haines, all that group. I admire them very much. It's funny, I had never seen a Mimmo Rotella in person until this weekend at Frieze LA.

Leonardo Bravo:

What was that like?

Edgar Ramirez:

I couldn't walk away from it! It was really nice to be able to have access to a painting like that because I don't know where there are many works of his here in LA, if there are any. And I really admire that sort of, or at least from the piece that I saw, it seems sort of violent. And there's a common thread, I'm very much interested in this idea of when I'm thinking of these rips, I'm thinking about sort of exposing or showing things that are there and that are overlooked or people turn their eyes from, not wanting to think or talk about it.

Leonardo Bravo:

It obviously sounds that you are incredibly observant and present in your community and observing these social, economic, cultural changes and how they're represented by the surroundings. I would assume that it's not only neglect but there's also perhaps a sense of truth, of beauty, of joy that is found in the community, that you've been able to observe or be part of that?

Edgar Ramirez:

Yeah, I think…I think a lot of times when people look at my work they talk about beauty.

Edgar Ramirez:

And to me it’s more from a standpoint of intuition, because I am immersed in this culture and these communities, and what I see is a lot of these people that are really proud of what they do. Especially when it comes to their job identity, and a lot of these jobs are things that you might never even think about, like making credit cards for example. Just being around these people there's this sense of pride in what they do and where they come from and why they're here, why they immigrated from their home countries to create this better life for their families. I think it comes from that kind of viewpoint where it's this idea of perseverance or being able to overcome these circumstances and create these opportunities for the resources that are lacking in these communities.

Leonardo Bravo:

And sometimes it's creating something out of nothing. I think that perseverance leads to an incredible sense of imagination.

Edgar Ramirez:

Absolutely. Something that I think about a lot, but I don't really talk about is this opportunity to have access. I think if art was more accessible in the way it was for me when I entered Otis. If art was more accessible at a younger age what would that do? I didn't at that time know that art was something completely different and I had no understanding that it existed the way it did. I think and I hope that we're working towards that as a whole, to better these spaces for future generations.

Leonardo Bravo:

Well, it sounds like that perseverance that your parents had, that your mother had, was passed on.

Edgar Ramirez:

My parents came to the US in the seventies and their story, the way they tell me that they got over here, makes me think of that. My mom, my mom came over here while she was pregnant with my brother, I think seven months pregnant, and she had to endure this journey of having to cross the border, and just like thinking about that. I guess the way I look at it, the problems that I have are, you know, they're kind of nothing.

Leonardo Bravo:

That perseverance is starting to pay off. Your work is being paid attention to. You're showing with Chris Sharp Gallery. How is it navigating the art world now? There's the art market and, there's this sense of all of a sudden more attention is being paid and probably you're having to think about your work and more demands on it.

Edgar Ramirez:

It's been a great time for me to think about these things. Being in art school, we had some talk about it here and there, but it's not really emphasized or focused on in terms of an art career or profession. It feels really nice to have people looking at the work and to have the support of a gallery. And to me it's related to these issues that I'm talking about. I want to be able to maintain this dialogue within the art community, and I'm hoping I can have the opportunity to show more in other places. I'd love to show in Berlin, in New York, and Shanghai or wherever.

Leonardo Bravo:

How are you thinking in your own sense of connecting to community building, giving back to community and maybe potential involvement in lifting up the next generation. Are you thinking about that?

Edgar Ramirez:

I do think about that. At this stage I'm not really sure how to do it in a way that's gonna be impactful, but I also feel like I just need to take a step and perhaps join a community organization that can direct me in the right path.

But I think it is important and I really want to do something where I can build a space to encourage children and younger people to get into the arts. I think about it in terms of what I lacked and I'd love to involve a community in some way to ask these questions about why things are the way they are, and how to create a conversation about these things from a younger perspective.

Leonardo Bravo:

The other part of that, is that you as a role model for communities is such an important component, especially for children and youth from our communities that have similar struggles and challenges, to see that role model of what you represent. Because you represent possibility, you represent that sense of opportunity for communities of color, and I think that's incredibly transformative to be in that space and to represent that.

Edgar Ramirez:

I think that's amazing. I mean, thank you for saying that. I don't know if I've ever thought of myself as being a role model. But I’ll definitely take it and I definitely wanna give back.. I want to be able to do like others before me have. I look at artists like Lauren Halsey and what she's done in her community too. And it's just like, maybe I just need to go out there and do it.

Leonardo Bravo:

And sometimes it's small gestures, it doesn't have to be large scale. You can dream it big but it's about your own capacity. And just from everything you're telling me and hearing your story, I think there's so much potential there for you to have that kind of impact, that sense of agency with folks.

Leonardo Bravo:

What's inspiring you right now? What are you admiring either in the arts, in music, books, or just your own personal life?

Edgar Ramirez:

I'm always looking at different art or revisiting artists that I hadn't thought about in a while. It's always changing but there's a constant of artists that are really meaningful to me. For example, James Turrell and what his work conveys to me, particularly the Skyspace works. I think about them very often. They feel serene and sublime, and it's kind of interesting because I had this thought last night about this idea of violence and serenity and combining them both. I mean, they seem like they shouldn't be attracted to each other.

I also write a lot on my thoughts and practice. And I’ve been thinking and writing about the monumentality of the works of some of the Light and Space, Minimalists, and Land artists, and being immersed in them and this idea of the sublime, it’ something that I think about a lot.

Leonardo Bravo:

That's fascinating you would say that because your work is so deeply enmeshed in socioeconomic conditions, and as a reflection on that you're bringing up this sense of tranquility, serenity, the sense of awe, the awesomeness of nature and what that can do. Light, atmosphere, colors, sounds, you know, sensorial experiences!

Edgar Ramirez:

I guess it's just an avenue. It's an avenue that I have to explore more to gain a better understanding of these ideas and what they mean to me. There's so much to learn from and that's where I'm at. To learn about what I'm interested in, taking it slow, a day at a time. And it's kind of nice.

Leonardo Bravo:

Well, Edgar, it's been a pleasure, man. I really appreciate these moments and it's so good to get this little snapshot into your creative process and the thinking. So truly appreciate your time.

Edgar Ramirez:

I appreciate you and being part of this. Thank you.

https://www.eramirezart.com/

IG: @_e_ramirez_