Kaleidoscopic No 1: Ramon Tejada

a fun and freewheeling conversation with the multidisciplinary designer and educator

This is the first launch of Kaleidoscopic Projects on SubStack highlighting a broad community of peers and creative makers that are pushing forth a more interdependent and equitable way of being in the world.

Hope you enjoy these lively conversations and look forward to your support, responses, and suggestions!

Kaleidoscopic No 1: Ramon Tejada

Ramon Tejada is a (New Yorkino / Afro-Caribbean / American) designer (as Estudio Ramon) and educator based in Providence, RI. He works in a hybrid design/teaching practice focusing on collaboration, inclusion, unearthing and the responsible expansion of design a practice he has named “puncturing.” Ramon is an Assistant Professor in the Graphic Design Department at risd. IG @rat93

Leonardo Bravo

Okay. So I'll do a little intro, Leonardo Bravo from Berlin talking to Ramon Tejada in Barcelona. We are doing a little convo about your multidisciplinary practice, your approach to design as a much broader set of approaches and connected to the purpose of this new project that I call Kaleidoscopic Projects, which is a way, to highlight practitioners that are looking at radical ways of world making, of seeing our world in more collective, more collaborative ways. So thank you, Ramon. Congratulations to you and your work!

Ramon Tejada

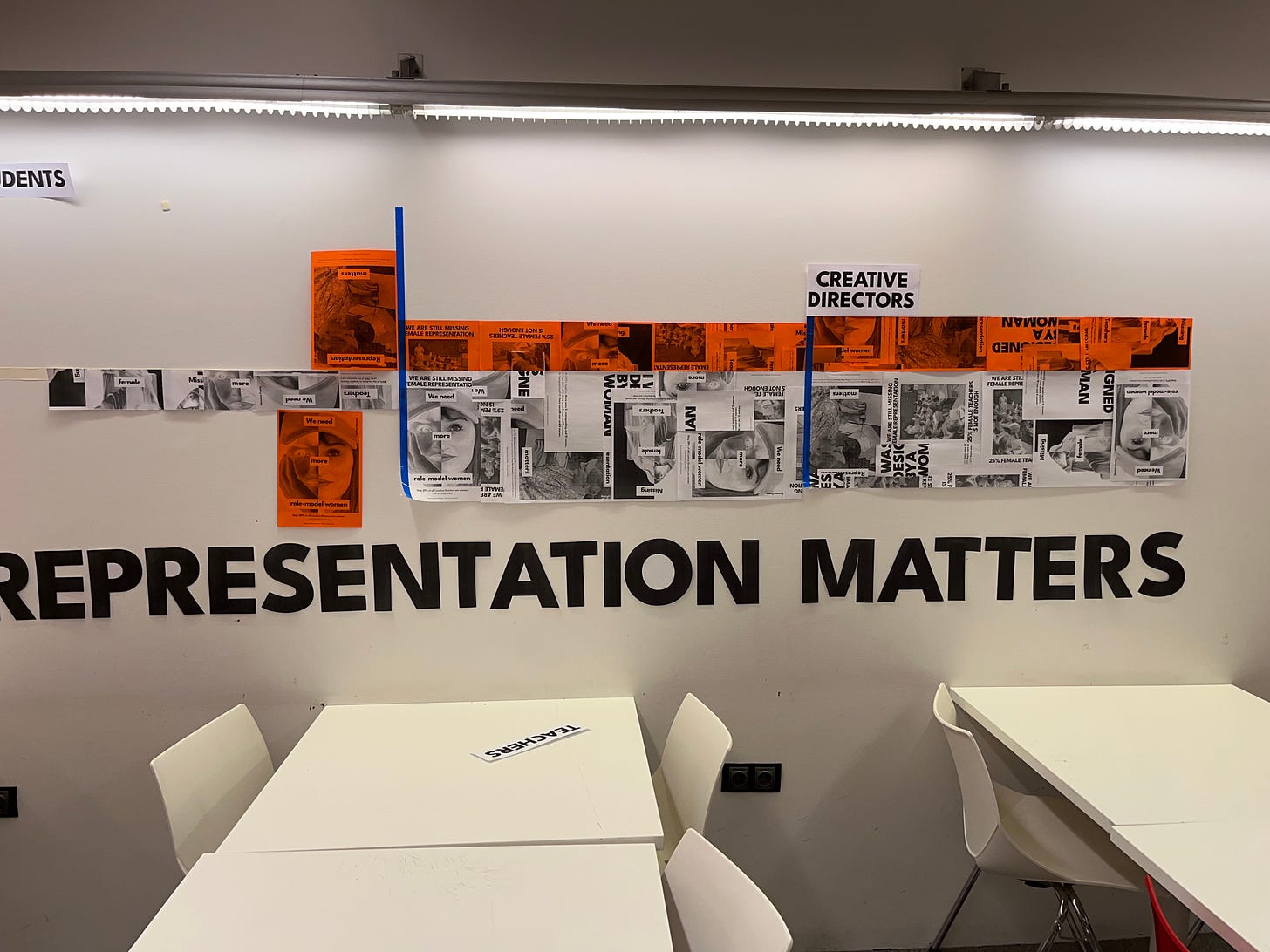

Oh my God. Thank you. I am in Barcelona now where normally I'm not, but I'm here for a few days trying to be a student for a little bit to make some stuff at ELISAVA, the Barcelona School of Design & Engineering in a workshop with Manuel Krebs.

Leonardo Bravo

Oh nice. I wanted to start actually from the beginning. And I know that you're originally from the Dominican Republic and to hear a little bit about what that experience was like being from the the island, specifically as it relates to your sense of aesthetics, to your sense of feelings, your sense of seeing the world, your sense of seeing society in a way.

Ramon Tejada

Yeah. I mean , I was born there. I grew up in New York, mostly because a lot of Latin families immigrated to the US and most of my life has been there honestly. I think that is something that I'm interested in digging into, but the version of it that I've come to terms with and realize is that I'm interested in digging is the New York slash Dominican part, because that is the part that to me is more relevant. The Dominican Republic, my parents retired there, they live there. I have a very complicated relationship to that place. I don't really know it. I feel uncomfortable saying that sometimes, cause I just don't know it. And there's a lot of, there's a lot of sort of cultural things that I just, I have disagreements with the way the culture functions, the machismo and the culture is a bit too much for me.

Ramon Tejada

So, and I don't know what that means for the things that I aesthetically navigate to. I haven't until recently started thinking about that but realized maybe in the last three years that I started to realize, I kind of need to explore that. What does it mean to grow up in New York city when the sounds, the sites, the food, everything that you sort of grow up with are totally different from what's out there?

Ramon Tejada

I've been thinking about what that means. I've been thinking about sort of the way color manifests itself in the Caribbean. I've been thinking about lettering a lot instead of typography and that expressiveness and that colorfulness and that sense of really organic composition that manifests itself there because of the way the land is and the way that things are, the way the food...I'm big into food. So I think the way the food is there in the Caribbean, or in other places that I really love. I think the food is like the way to look at like, what is going on here. And I think I've gone into it by looking at it in other places, like I've gone to Mexico a lot and I love Mexico.

Ramon Tejada

I'm like, what is my problem? I feel very comfortable in Mexico. I feel really comfortable in Mexico City and in Oaxaca. There's something about the way the people are, the land, everything just feels like, okay -- I feel really comfortable here. And again, I've been there many times for extended periods of time, which is really fabulous. And that sense of the organization of things, there's something there, and the food and the stories that the food tells. But when you start to dig through, it's just so incredible. And that I'm trying to think about that in the context of the Dominican Republic as well.

Leonardo Bravo

That is really intriguing to me because you are telling stories through a very experiential and sensorial way of seeing the world. Like when you are in those countries you are right in, in the global south, we can say. Which is so different than the lens or framing that happens with your design training, which is very rigorous, the rigor of the Bauhaus. The rigor of design by applying that sense of logic, that sense of analysis and, and thinking how important it might be to not let go of one or the other, but how these things begin to balance out or become different lenses that are applied, you know?

Ramon Tejada

Yeah. Or when, when do you need to use certain things, right? When does that quote unquote education apply itself at education? It’s very rigorous in terms of generating a little pixel that sits on a field, of what in graphic design, a lot of times is referred to as white space, but which I have said, we are done with white space, please stop talking about white space. Like we're done with that. And thinking and just privileging that as the right way to do things. Or that is the, the absolute essence. The reductive thing that encompasses all of the ideas. And then I'm like, well, I come from a culture where it's about excess and beauty and that excessiveness, which spills out and it screams, and it’s loud, and it works so beautifully. And I don't know that there’s this binary anymore. We're in a cultural moment where like that yes, no, right wrong, good, bad binary doesn't work at all. So, you know, I really, I start to think about that. And then also in thinking about teaching and that's all about possibilities, right?

Ramon Tejada

Like a student or somebody who's coming up or even friends when we're talking about the way that everything needs to be more expansive than just being reductive. But I get it because we all were educated in this sort of pseudo Bauhausian reductionist thing, or at least the version that was given to us. When I was in Berlin last summer and went to the Bauhaus, which I'd never been to, I took a train. I didn't even realize it was that close to Berlin, it is, it's only an hour and 10 minutes away. And I remember walking in the building and going, oh my God, of course, of course the energy in this building is incredible. And I remember going to the museum, of which there’s a show on the second floor, and I was really interested in seeing the students’ work of which there is a portion of and realized what they were doing -- they were just experimenting and trying all sorts of crazy things. Half of those things look like student work. They don't necessarily work, but they're exploring ideas. And then also seeing that they weren't necessarily into reductionism at all. They were kind of just trying different things. But we inherited a lineage based on reduction, like reduce everything to the essence which I don't think it's possible all the time.

Ramon Tejada

And that's just more pluralistic thinking, which again, going back to sort of what you were saying about the global south, when you think about, or you do research about the global south — and thinking primarily of Arturo Escobar's book and having listened to him — in most of the global south things work in multiples. There's this pluralistic thinking of the work, it's all these gears, like moving through each other, right next to each other, there isn't just one thing. It's like all of these beautiful cosmologies. I think it's a term he uses that coexist and have coexisted for millennia way before the sort of rational thought of Europeans came in. Things worked already so beautifully. So there's this wonderful, gorgeous web and flow of multiple ideas and languages and icons and symbols and all sorts of things. And I love that. Because that's messy and complicated.

Leonardo Bravo

And so tell me a little bit about that, because, when you're speaking those words, I'm like, yes, that's it, and it relates to a statement that I was reading where you talk about your work and this whole sense of puncturing that you describe. I mean, you really, I think have it , have something there, and you talk about.."unearthing, shifting the glance and decentering, giving agency, being vulnerable, making mistakes, thinking about our communities, thinking about mom, dad, and grandparents as your neighbor are chosen families." And I love that. I mean, when you're thinking about pluralities and this ebb and flow, it's that, you know, those very messiness that entangle with each other.

Ramon Tejada

Yeah. For me, in relation to that, there's probably a GIF that you saw that I found that was like, this damn that broke. How it all comes out to me, that's like, I feel like what design needs to be. And I know that's a big shift for people to think about, but I think about the puncturing part, part of it is, like to actually just like make massive gaps in whatever it is you're making, whether that's a ginormous hole that allows for all sorts of things, instead of like holding it back in this very shiny little reflective object, and oh, look how cool it is. Because I have those chairs too. Okay. I have Eames chairs. I love that stuff. People are like, you hate all that. I'm like, have you been to my house?

Leonardo Bravo

I'm drawn to the work of designers because of context and you have to think of an external factor, which a lot of times it's a client. But many times it's also a set of conditions about community and the worlds we want to see. Let's talk about that as I find your ideas so exciting and intriguing in terms of, and this is something that I deal with students, what is the world that we want in front of us, what's the kind of world making that we hope for. When that seems, perhaps daunting…like this sense of these new cosmologies or constellations, right. How do we begin to do that work? And, you told me a little bit when we were conversing before, it's this notion of making with others. But what does that look like and how does design begin to kind of be a set of activities that it is about making with others? I find that super challenging and intriguing and, and amazing to be in that space.

Ramon Tejada

It's really hard and challenging. I don't think I have all the answers. I think it's probably like a lifelong process because we have over a hundred years of a process that has been given to us as to how this is supposed to work. So it's gonna take a while to get through, I think that it requires a lot of humbling and forgetting what you know. You need to go in that space of community and not know jack crap.

Ramon Tejada

I was listening to this podcast, Scratching The Surface, which is this sort of design podcast that Jarrett Fuller does. And he had this interview with the architect, Deanna Van Buren, and he did it in 2020, like during the pandemic. And she's incredible. And she thinks about designing — she does a lot of non-for-profit work in Oakland, in California — and one of the things I was really taken aback that she said, which is, designers, when you go to do this work, you need to assume that you don't know anything, you're one part of the pie. You need to forget that you think you are the pie. We don't know anything. She's like, if you really wanna make change in communities go and hang out with community organizers. Those people who have been doing the work in those communities for years. Forget about hanging out with a bunch of designers, designers haven't done anything. And I would say, that is so right. It requires a lot of conversations. It's requires a lot of humbling down. It requires a lot of forgetting everything we learn in school. It requires forgetting about composition and it requires forgetting about typography. It requires that you forget about your definitions of what colors mean. It may not mean that at all in that community, and I think that humbling part is really difficult for all of us. Cuz we're in a culture where you're not supposed to put yourself in that vulnerable position where you don't know anything. Because then you're weak. Or you're just, you know, like not an expert anymore. And I think that that's been challenge that I think that's a big challenge, but that's one way that I think about it. But it requires a longer investment. I think it's not just a one off you can't just go to one thing and you're done -- it's developing the relationships

Leonardo Bravo

Tell me about your work with students especially as you push for a more, I mean a lens that's all encompassing on BIPOC identity. And how do you rethink the practice to say like, when we think of being designers, we actually need to read people like… bell hooks.

Ramon Tejada

Yeah. oh my God. Shocker. Like this incredible woman who wrote all these books and they're so accessible. I mean, she had a very broad and deep vocabulary and I'm like, you read them and you're like, this is so common sense.

Leonardo Bravo

And her language is so clear. It's crisp. Yeah.

Ramon Tejada

It's like, you know, I don't have to pull a dictionary up and she knew how to use a dictionary. Of course she did. You know, she knew those big words, but she's like, maybe you don't need to use that in a certain context, right. Like I'm trying to reach you. I'm not trying to like show you how excitingly amazing my vocabulary is. I think my job as a teacher is to open possibilities for students and to realize that they can do many things. I think it's also really important for them to realize that they have to make work that they love and they enjoy. I can spot work from students these days that looks like they just went through the motions, it was just boring. They were not interested. There was no joy in it. And I love it when several students have told me that I've given them their favorite critique, which is I have, it's nothing formal. It's just like, are you having fun doing this? So I think it's helping students realize that there's so much value in the stories they have and carry. And that they don't need to go into a history book and start talking about stuff that they think you should know that, but that shouldn't be the thing that you're only doing, but it should be your choice. If that's what you wanna do, I want you to also be aware that there's this other thing that you may wanna do, and you may wanna explore, which might mean you're looking at pictures of you being a kid with your grandparents or your aunt or your cousin or whoever.

Leonardo Bravo

It's interesting because the paintings I make are geometric abstractions and I've recognized over the years that the catalyst for this work are the Mapuche indigenous textiles that my father used to collect in the south of Chile, and these visual forms and patterns that I was fascinated with as a three or four year old, that you might also say, this is Bauhaus or this is mid-century, but it's not, these were my first visual symbol systems.

Ramon Tejada

But the thing, the reality about that is even like, you know, in art and design, we go into, well, this is the Bauhaus -- that was not the Bauhaus. And that's Okay. At the Bauhaus school they saw some of that work as well. Yeah. Right. Like they were inspired by some of that work in Latin America and they were looking at the geometry, but there was a geometry from all over the world. There’s this designer Vanessa Zúñiga Tinizaray who is from Ecuador and she does all this incredible work. And I saw one of the talks that she gave, she was talking about doing her thesis, which she did in Argentina. She was looking at the geometry and the way that the same geometrical forms were appearing in Ecuador, the Andes, and the whole indigenous area. And then in Africa and then in Asia at the same, and in the middle east at the same time. But they composed them differently and the visual forms were telling different stories. Instead of just like, we always go back to well, that's Bauhaus. It's like, no, the Bauhaus is a baby next to some of these deeply historical cultural resonances.

Leonardo Bravo

They're so ancestral, they carry so much history.

Ramon Tejada

Absolutely. Thousands of years. Thousands years. And you know, like Annie Albers, didn't invent textiles in pattern. Okay, and I love Annie Albers. Better than her husband. I think more interesting than her husband. But also again, that trip to the Bauhaus school that I went to last summer, this place they had was the library at the Bauhaus. And I was like, okay, this is gonna be interesting. And the curators did this great job of sort of contextualizing things for the present. And they were saying that there were two librarians at the Bauhaus in the 1920's who were very interested in non-European forms and ideas because they thought that was the most, the most relatively important work for designers and artists to look at -- it was not in Europe but was coming out of Africa and south America.

Leonardo Bravo

Well, it's a little bit of what you've been saying about this actual puncturing. I mean, the narrative is not linear….that the narrative is so much more inclusive than what we give it credit to.

Ramon Tejada

You know, I was working with Silas Monroe and doing this, this BIPOC design history class and he did a black design in America with and I did this incomplete stories of Diseno Latino Americano and I was like, you know, I'm like 12 talks in... And I can't cover it all.

Leonardo Bravo

You're just skimming it.

Ramon Tejada

Again, because I'm like, there's no way. I'm like, you know, when you're thinking about Latin America, it's just a ginormous way of looking at things. And then you have so many cultures and subcultures of subcultures and within each subculture, things can change radically. And that's incredible. So there's back to that idea of pluralities. Like you're talking about at least for Latin America, a continent you know, like I, when I say America, I refer to the whole continent.

Leonardo Bravo

The whole thing, that whole thing. El Sur to El Norte. Thank you.

Ramon Tejada

You have an entire continent, that has hundreds, possibly thousands of ways of looking at the world. People that inhabit that same continent and have lived and have been told that you're not supposed to look at art this this way, because this is wrong and this is craft and this is kitsch. Yet we all run to the tours, go look at it, take a picture, run back to our studios and then start copying that. Without any thought. Right. Like, and we've seen that example versus sitting down and going like, wait a minute, I love geometry. Like you just say it. I love geometry. And I'm thinking, oh wow. Okay. My dad. Yeah. That's incredible to think about, you're actually having a conversation with your dad.

Leonardo Bravo

Yes, deep and ancestral!

Ramon Tejada

And it that case, your dad he was trying to show you stuff and you're like, what's wrong with me? You know, you might have been too young or it wasn't something that held your attention, but I think it's really interesting to take the time to do that. And I find that with a lot of the BIPOC students and the amazing work that they're creating that is really you thinking outside of the boundaries of that European tradition we've been given as designers. And also just giving them that space. Sometimes you just have to give them the space to actually try it. And some things may not work and it's okay. Like it doesn't need to work that way. I love that and I feel like that's sort of my job is to make space, and point them in certain directions to free them up and sort of say, yeah, we're gonna work for a month. We're gonna work on this thing and I just, I don't know what you're gonna make. You don't know what you're gonna make, but I want you to investigate it, explore it, and see what there is and dig into it. And we're gonna talk about it cuz you need to have the space to talk about it, to make it, to try it. So that's sort of how I see myself, if that makes sense.

Leonardo Bravo

That's good. It's beautiful, and open, and puncturing in its own way. Ramon, this has been such a treat to have a conversation with you full of joy and flow. You know, in my dream of dreams, I wanna set up a space here in Berlin where design and print based works on paper can be featured and I would love to stay in touch towards that.

Ramon Tejada

That. Yeah. Let me know. I mean, talking about a really awesome city, I love Berlin. It's so good! Such a great artistic city, but I feel like it's also a city that's riddled with possibilities everywhere. Like cuz you can actually, I think it, it's been very successful at turning itself into a productive site, a place where people can be productive in terms of their creativity and culture. So yes, excited to hear more!

AMAZING READ! Thank both of you! You for put Vanessa Zúñiga Tinizaray back on my radar!